The partial collapse of a new bridge in China’s Sichuan province this week riveted a global audience with the spectacle of disaster. The greater drama is China’s breakneck hydropower expansion.

Introduction by Lisa Peryman for Probe International | English translation by Eleanor Zhang (Three Gorges Probe)

The spectacular and shocking collapse of a section of southwestern China’s Hongqi Grand Bridge on Tuesday afternoon was captured and circulated on social media worldwide as it happened.

This bridge, a vital pulse that connects central China to Tibet, had been completed just months earlier in an area with a known susceptibility to landslides in a region with a history of seismicity, including a series of earthquakes in 2022 that forced the evacuation of more than 25,000 people.

One might ask: why was this route selected at all?

Renowned Chinese geologist and environmentalist Fan Xiao illuminates, as no one else has, the factors that led to the Tuesday collapse. Fan moves beyond the initial trigger of a landslide to explore the event’s relationship to nearby megadam—the Shuangjiangkou Hydropower Station, which also happens to be the world’s tallest.

Did Shuangjiangkou play a part? Yes.

Dam Déjà Vu

Not only was the bridge located on an unstable slope that had not been adequately assessed for geological hazards, argues Fan, the landslide on the right bank of the bridge was exacerbated by rapid water level increases in the Shuangjiangkou Hydropower Station reservoir. The phenomenon of rapid rise in water levels heightening the risk of geological disasters is nothing new and has been observed elsewhere, including Three Gorges Dam.

Tuesday’s disaster, he says, presents another reminder of the dangers associated with rapid reservoir impoundment, underscoring the urgent need for improved safety measures in hydropower projects, and thorough geological hazard risk assessments before major construction projects are undertaken, particularly in geologically unstable areas.

However, in a country where the rapid expansion of hydropower led to the completion of over 95,000 reservoirs last year, and with more large-scale projects in progress—including a new “world’s largest”—will China’s next learning opportunity be as “fortunate” as the lesson of Hongqi? Given that this is a highly seismically active region, the future looks perilous.

Talking About the Collapse of the Hongqi Grand Bridge and the Shuangjiangkou Hydropower Station on the Dadu River

By Fan Xiao

Originally posted on “Heshan Wuyan” (Rivers and Mountains in Silence — WeChat Public account)

Overview of the Hongqi Grand Bridge and the Shuangjiangkou Hydropower Station

At around 16:00 on November 11, 2025, a landslide occurred on the right bank of the Hongqi Grand Bridge in the reservoir area of the Shuangjiangkou Hydropower Station on the Dadu River, causing the bridge to collapse.

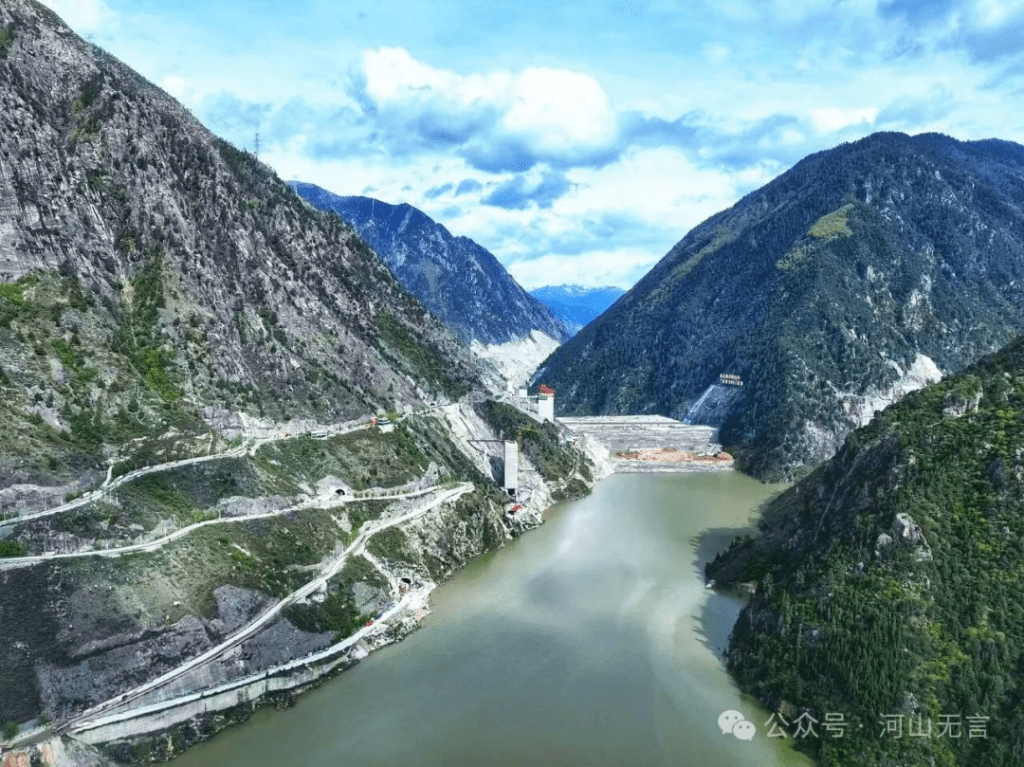

The Shuangjiangkou Hydropower Station is located at the confluence of the Duke River and the Jiamuzu River (Ma’erqu), the two headwater branches of the upper reaches of the Dadu River. The station’s dam sits just downstream of their confluence. The collapsed Hongqi Grand Bridge was located on the Jiamuzu River within the reservoir area. It is a newly built bridge on a rerouted section of National Highway 317, constructed to replace the original alignment of Highway 317 and the original Jiamuzu River bridge, both of which were submerged after the reservoir was impounded.

Because reservoir impoundment would raise the water level substantially, the location of the Hongqi Bridge was set much higher than the old bridge, making it a grand bridge with a main span of 220 meters and a main pier height of 172 meters.

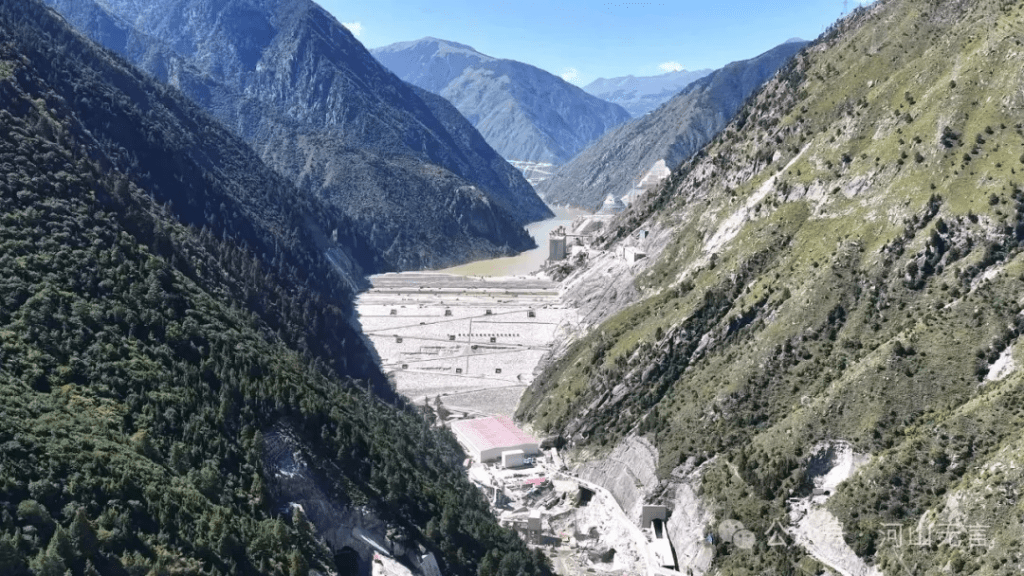

The Shuangjiangkou Hydropower Station is the fifth of 27 cascade projects planned along the main stem of the Dadu River, counting from upstream. Its 315-meter-high dam is currently the tallest in the world. The reservoir has a total storage capacity of 2.897 billion cubic meters, making it the second-largest reservoir on the main stem of the Dadu River after the Pubugou Hydropower Station (with a total storage capacity of 5.39 billion cubic meters). The station’s installed capacity is 2 million kilowatts.

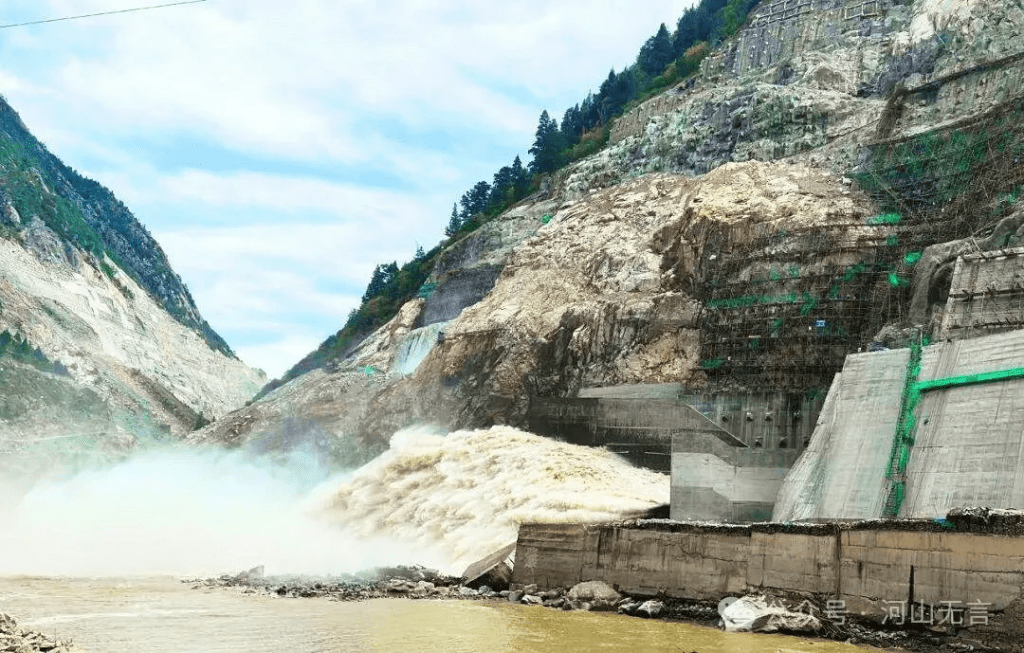

On April 3, 2025, the Shuangjiangkou Hydropower Station began its first phase of impoundment, which was completed by May 1. During this period, the water level rose by more than 90 meters and the impounded volume reached 110 million cubic meters. On October 10, 2025, the station began its second phase of impoundment. The water level rose by more than 70 meters, with an additional 660 million cubic meters stored. Over roughly seven months across these two impoundment phases, the water level rose by more than 160 meters, setting world records for both the rate and magnitude of rise.

The previous record holder was the Jinping-I Hydropower Station on the Yalong River (dam height 305 meters), where the water level rose by 148 meters between October 2012 and July 2013, a process that induced a relatively dense cluster of moderate earthquakes.

Against the backdrop of inherently unstable geological conditions in high mountain gorges, rapid and large increases in reservoir water levels make the trigger of landslides, collapses, and other geological disasters highly possible. Similar cases have repeatedly occurred at many large reservoirs, including the Three Gorges.

The rate of rise and the total range of water level changes at the Three Gorges Reservoir cannot be compared to those at Shuangjiangkou. Yet after the first-phase impoundment of the Three Gorges Project to 135 meters, it induced the Qianjiangping landslide with a volume of 24 million cubic meters. In September 2008, when the third-phase impoundment pushed the water level toward 175 meters, the reservoir area entered a period of high geological disaster incidence. In the impoundment–drawdown stages of 2008–2009, 243 geological disasters occurred in the reservoir area, of which 167 were newly emergent sudden events, accounting for 68% of that total.

In response, the Changjiang Water Resources Commission required that daily water level fluctuations during impoundment–drawdown periods be kept within 0.5 meters. As a result, conditions in the 2009–2010 and 2010–2011 impoundment–drawdown stages became more stable, with the number of disaster (or near-disaster) events dropping to 16 and 13, respectively.

Background to the Landslide on the Right Bank of the Hongqi Grand Bridge

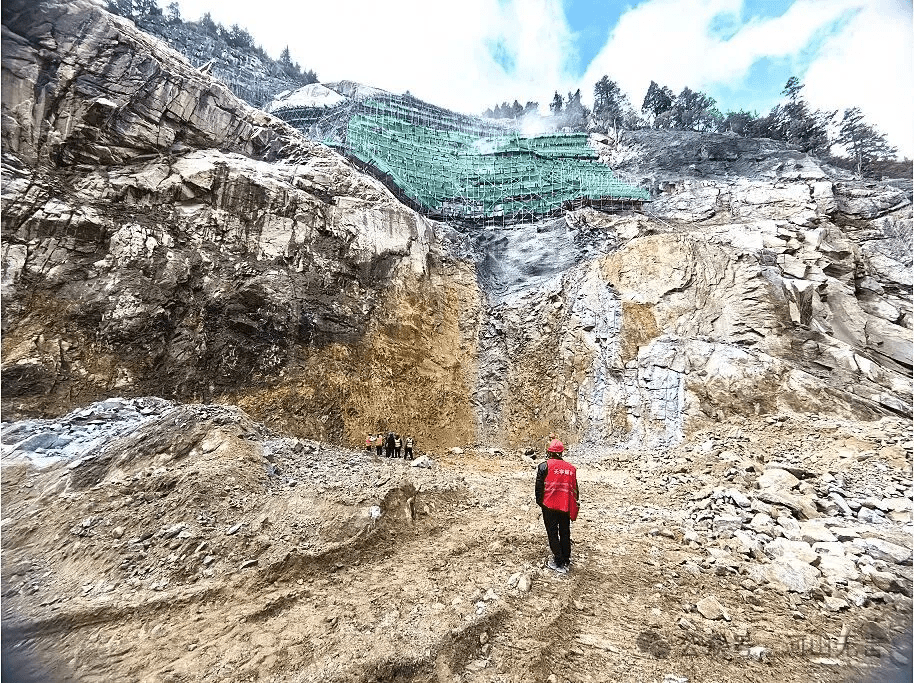

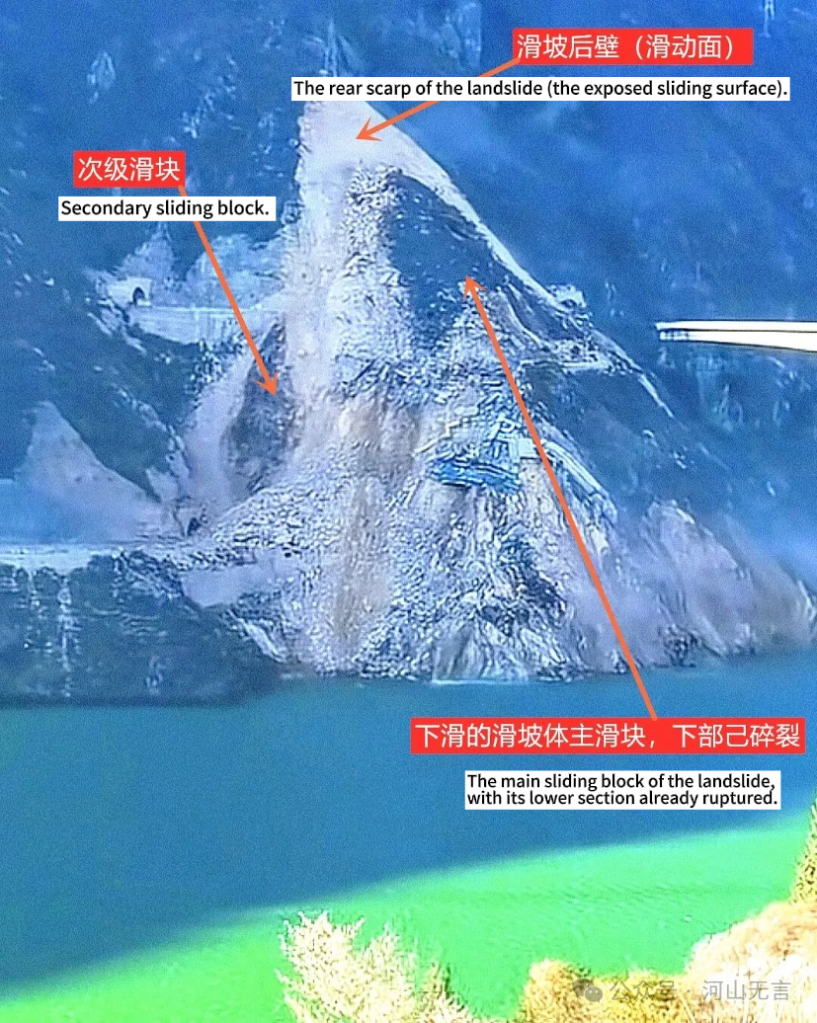

The landslide on the right bank of the Hongqi Bridge originated in a potential landslide mass on a steep slope. Due to gravitational disintegration and weathering, the slope rocks had already been shattered, consisting largely of relatively loose and unstable colluvial deposits. The rerouted Hongqi Bridge on National Highway 317 was sited not only on a high, steep hillside that was more unstable than the site of the old bridge, but also directly atop this potential landslide body.

On the one hand, slope cutting during construction increased the height and steepness of the exposed slope face, while the load imposed on the slope by the bridge structure itself further heightened the risk of instability. On the other hand, the rapid and large rise in water level in the Shuangjiangkou Reservoir was very likely an important factor in triggering the landslide.

The bridge pier on the right bank of the Hongqi Bridge was located on a steep, fractured slope. The foundations were not deeply excavated and were partially hanging, with no slope protection works in place. Even without a landslide, there were already safety hazards.

The process of the Hongqi Grand Bridge collapse and the characteristics of the landslide on the right bank

At the initial onset of the landslide, a rupture occurred along the sliding surface, sending up dust. At this stage, the landslide mass had not yet accelerated downslope, and deformation of the bridge was limited.

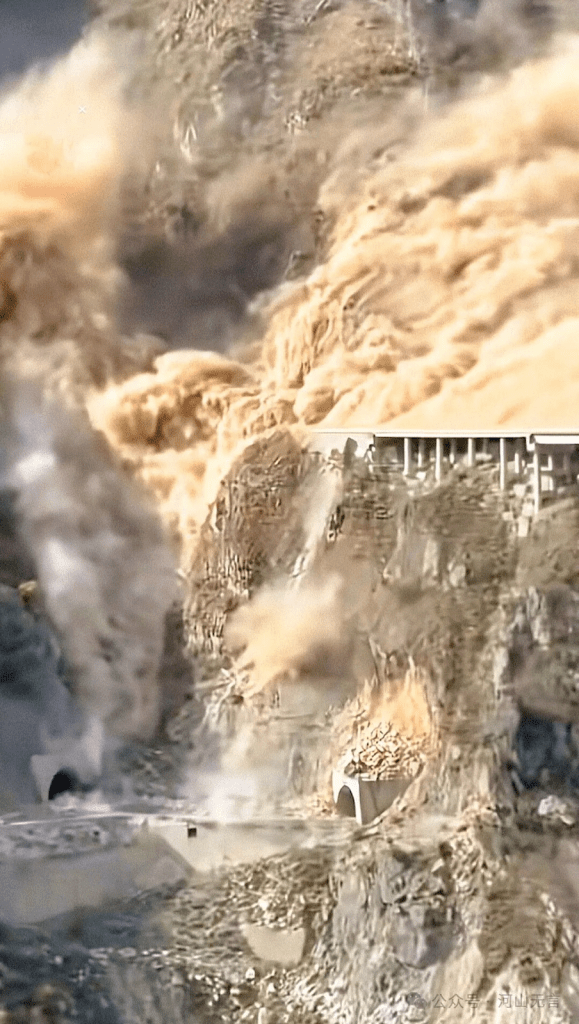

As the landslide began to accelerate, cracking occurred at the edges of the sliding surface and in the lower part of the landslide body, greatly intensifying the dust. At this point, the bridge already showed obvious deformation. As the landslide mass rapidly moved downslope, the bridge fractured, tilted, and ultimately collapsed completely.

After the rapid downslope movement ceased, the overall structure of the landslide could be observed from a distance.

Lessons That Should Be Drawn

Before the construction of any major project, a “geological hazard risk assessment for the construction project site” must be carried out. The Dadu River canyon is inherently a region prone to geological disasters, thus assessments there should be conducted with particular caution and in great detail.

Were the potential landslide body on the right bank of the Hongqi Grand Bridge and related geological disaster risks thoroughly investigated and evaluated? Was the siting of the Hongqi Bridge subjected to an objective and scientific argumentation process? During bridge construction, were the associated risks adequately controlled for and hazard prevention measures undertaken?

According to relevant reports, early warning signs such as rockfalls had already appeared on the right bank of the Hongqi Bridge in the first half of 2025. Cracks were discovered on the bridge deck the day before the collapse, and traffic control measures were implemented. This is an outcome that can only be described as fortunate. In fact, large landslides of this type typically exhibit multiple warning signs long beforehand. The failure to include this potential landslide body within the scope of geological hazard investigation, monitoring, and early warning mechanisms is a clear shortcoming.

Large hydropower reservoirs are highly prone to triggering geological disasters during impoundment periods. Many cautionary precedents already exist. Under conditions of such extraordinarily rapid and large water-level rises as at Shuangjiangkou, there is an even greater need to attach importance to the monitoring and prevention of geological hazards in the reservoir area. At the same time, the rate and range of water-level increases should be regulated to avoid rapid, large-scale impoundment driven solely by the pursuit of power generation and other interests, which would in turn create serious risks to the geological and environmental safety of the reservoir region.

Categories: China's Dams, China's Water, Dams and Earthquakes, Dams and Landslides, RIS, Three Gorges Probe