A blockbuster report by Chinese geologist Fan Xiao uncovers the deceit, censorship and raw force at play in the resurrection of a massive dam project in a geologically complex region.

Foreword by Probe International

The topic of China’s rampant and unchecked hydropower development in zones and regions of high seismic risk is once again on the table after a series of powerful earthquakes rocked the southern Tibetan plateau in early January. The quakes follow on the heels of news China plans to revive a controversial hydropower project in the geologically complex area.

The scale of this proposal has reignited concerns about the region’s suitability to play host to such a high-stakes risk.

The report in English we present here by renowned Chinese geologist Fan Xiao—published on October 22, 2024 in Chinese—shines a light on the forces at play that made this proposal untenable when it first emerged as a potent consideration in 2004. Known then as the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project, Fan Xiao’s analysis demonstrates why the undertaking was and remains a resounding “NO” on every conceivable level: geologically, environmentally, economically, and socially.

Layered into the core of this assessment is a development of another sort: the opening up of China’s burgeoning environmental movement that has since been buried—not by the inundation of land for the creation of an artificial lake—but by the rule of Xi Jinping and his crushing impact on the nation’s civil liberties.

To that end, Fan Xiao’s gift for demystifying complex geological forces and interrelated hazards in the context of large dam construction is as much a geological exposé, as it is an invaluable account of social history. We see how a citizen-led campaign prompted Chinese authorities 18 years ago to suspend the Tiger Leaping Gorge project. The decision represented a shining victory for the country’s grassroots environmental organizations, social media and general public, and also revealed a moment of government flexibility: officials responding to the will of the people. That window has since been all but sealed by Xi Jinping’s rise to power, his crackdown on NGOs, his near-total control over social media, and his implementation of China’s Big Brother mass surveillance network.

Fan Xiao’s analysis further uncovers the deceit, censorship and raw force at play in the resurrection of what has been rebranded as the Longpan Hydropower Project, and the lie of what the Chinese Communist Party refers to as the “rule of law.” Incompatible with legal standards, national policies and public interest, the driving force behind Longpan is greed intensified by China’s current economic woes.

There is no reason to justify its construction other than political gains.

Four Major Hazards of the Jinsha River Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project

By Fan Xiao | English translation by Probe International

First published to WeChat on October 22, 2024 [since deleted by China’s censors].

Scroll to the end to download a PDF version of this document.

Under the influence of developmentalism, it is often assumed that anything—including your emotions, your land—can be compensated with money. However, the people living along the Jinsha River think otherwise. They say: “Even if you pave this river valley with gold, it cannot replace this free-flowing great river, nor can it restore our homeland!”

— Xiao Liangzhong

- Background of China’s Jinsha River Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project

According to China’s hydropower development plan, 27 cascade dams will be constructed along the Jinsha River, stretching from Yibin in Sichuan Province to Zhimenda in Yushu, Qinghai Province. This will transform the Jinsha River from a natural waterway into a series of connected reservoirs.

As of now, 12 hydropower stations on the middle and lower reaches of the Jinsha River (from Xiangjiaba to Liyuan) have been completed, while 13 planned stations on the upper reaches have seen partial progress. Among these, the Suwalong Hydropower Station has been completed, and six other stations, including Xulong, are currently under construction (see the table below).

Table: Overview of the 27 Hydropower Stations Along the Jinsha River Mainstream

| STATION NAME | DAM HEIGHT (METERS) | RESERVOIR CAPACITY (BILLION CUBIC METERS) | INSTALLED CAPACITY (10,000 kW) | CONSTRUCTION STATUS |

| 01 Xirong | – | – | 32 | Planned |

| 02 Shaila | – | – | 38 | Planned |

| 03 Guotong | – | – | 14 | Planned |

| 04 Gangtuo | – | – | 110 | Planned |

| 05 Yanbi | – | – | 30 | Planned |

| 06 Boro | 138 | 6.22 (8.37) | 96 | Under Construction |

| 07 Yebatan | 217 | 11.85 | 224 | Under Construction |

| 08 Lawa | 239 | 24.67 | 200 | Under Construction |

| 09 Batang | 69 | 1.58 | 75 | Under Construction |

| 10 Suwalong | 112 | 6.38 | 120 | Completed |

| 11 Changbo | 58 | 0.12 | 106 | Under Construction |

| 12 Xulong | 213 | 7.08 (8.47) | 240 | Under Construction |

| 13 Benzilan | 185 | 13.53 | 220 | Preliminary Prep |

| 14 Tiger Leaping Gorge (Longpan) | 276 | 371 | 420 | Controversial |

| 15 Liangjiaren | 81 | 0.0074 | 300 | Controversial |

| 16 Liyuan | 155 | 7.27 | 240 | Completed |

| 17 Ahai | 130 | 8.82 | 200 | Completed |

| 18 Jinanqiao | 160 | 9.13 | 240 | Completed |

| 19 Longkaikou | 119 | 5.44 | 180 | Completed |

| 20 Ludila | 140 | 17.18 | 216 | Completed |

| 21 Guanyinyan | 159 | 20.72 | 300 | Completed |

| 22 Jinsha | 66 | 1.08 | 56 | Completed |

| 23 Yinjian | 70 | 0.594 | 34.5 | Completed |

| 24 Wudongde | 270 | 74.08 | 1020 | Completed |

| 25 Baihetan | 289 | 206.27 | 1600 | Completed |

| 26 Xiluodu | 285.5 | 128 | 1386 | Completed |

| 27 Xiangjiaba | 162 | 51.63 | 600 | Completed |

Notes on the Table:

- The stations are listed in cascade order from upstream to downstream.

- Construction status is accurate as of December 2023.

- Reservoir capacities not in parentheses represent the volume below normal storage levels, while those in parentheses include total volume below flood-check levels. [Here, the normal pool level or NPL refers to the maximum elevation to which the reservoir surface will rise for ordinary reservoir operations. The maximum flood control operating level occurs during floods. It is the highest flood level temporarily allowed for the reservoir under extreme flood conditions and serves as the primary basis for determining the dam crest elevation (the dam height above sea level), as well as safety assessments of the dam. The reservoir capacity at the NPL is also smaller than the reservoir capacity at the flood control operating level. – Ed.]

- Dam height refers to the maximum height of the dam structure.

- Data is compiled from publicly available reports, government announcements, environmental impact assessments, scientific literature, etc. Due to incomplete public data, some fields in the table remain blank.

Particularly noteworthy is the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project on the upper reaches of the Jinsha River’s middle section. Highly sought after by hydropower developers for its potential to create a large regulating reservoir, this project has been a subject of significant controversy. Since 2004, it has faced strong opposition from local residents and various sectors of society, leading to its suspension.

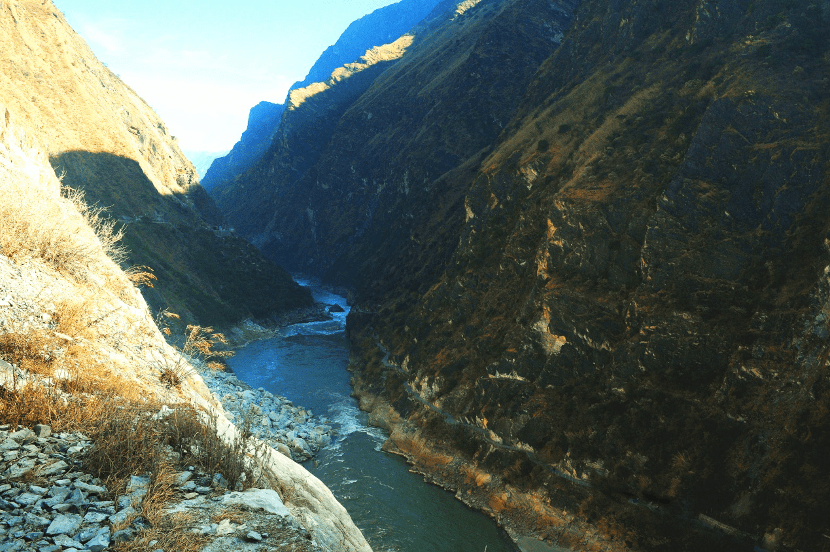

The Tiger Leaping Gorge extends approximately 23 kilometers, beginning at the confluence of the Xiaozhongdian River and the Jinsha River in Shangri-La City at its upstream end and ending at the old ferry crossing in Daju Township, Yulong Naxi Autonomous County, at its downstream end. Over this stretch, the riverbed drops about 213 meters, flowing through a deep canyon flanked by the imposing Yulong Snow Mountain on the right bank and Haba Snow Mountain on the left bank. The gorge, with an average depth of 2,500 to 3,000 meters and a maximum depth of approximately 3,800 meters, is divided into three sections: Upper Tiger Leaping Gorge, Middle Tiger Leaping Gorge, and Lower Tiger Leaping Gorge. Among these, the Upper Tiger Leaping Gorge is the most treacherous, distinguished by the iconic Tiger Leaping Stone standing boldly in the river’s center.

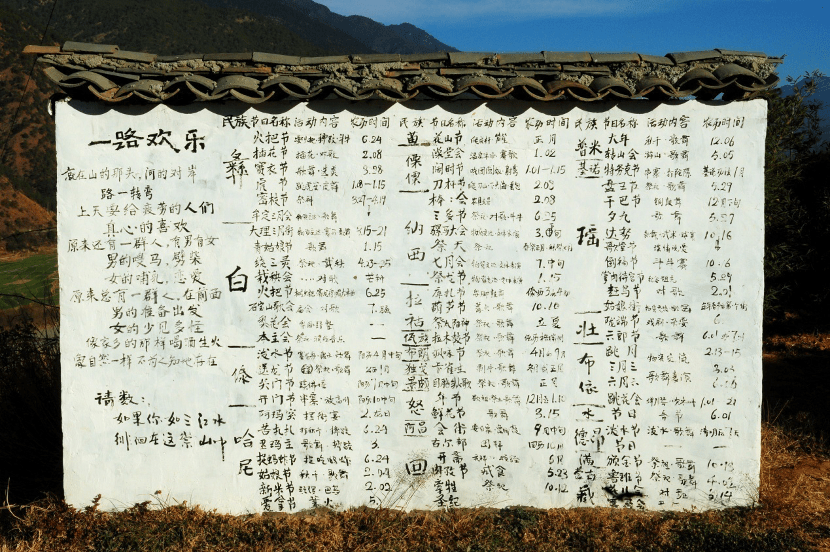

Upstream from the gorge entrance to Tacheng Township in Yulong Naxi Autonomous County lies the longest and widest valley stretch along the Jinsha River. This expansive valley stretches over 100 kilometers and encompasses key settlements such as Longpan, Shigu, Jinjiang, Judian, Shangjiang, and Tacheng. The region is home to a diverse array of ethnic groups, including the Naxi, Lisu, Bai, Tibetan, Yi, Miao, and Han peoples. Villages and farmlands densely populate the area, making it the most significant agricultural production zone within the Jinsha River Valley.

The wide valley section of the middle reaches of the Jinsha River offers a distinctive geographical advantage. By constructing a dam approximately 276 meters high near the upstream entrance of the Tiger Leaping Gorge, this natural bottleneck can be sealed, converting the gorge’s wide valley upstream into an immense reservoir with a storage capacity of approximately 37.1 billion cubic meters. This reservoir would be the largest among the cascade of hydropower stations on the Jinsha River and second only to the Three Gorges Reservoir on the Yangtze River, which has a capacity of 39.3 billion cubic meters. It would play a pivotal role in regulating the operations of the downstream cascade hydropower stations along the Jinsha River.

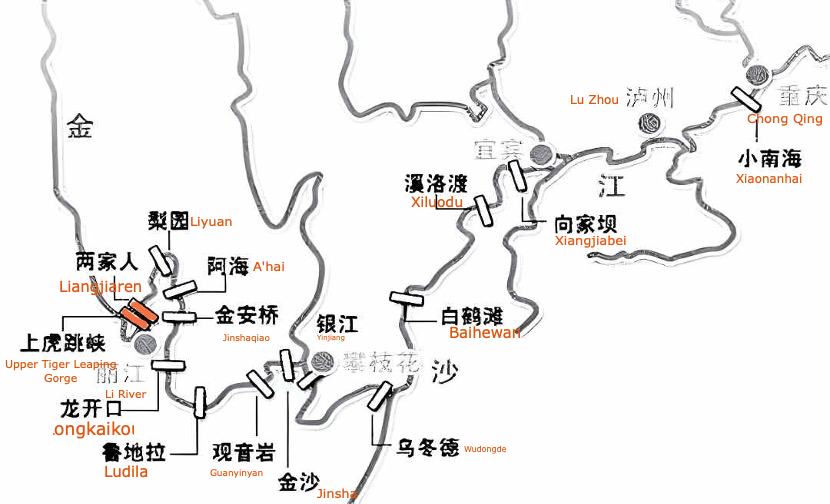

The Tiger Leaping Gorge hydropower project actually encompasses two hydropower stations: the Upper Tiger Leaping Gorge and the Liangjiaren. The Upper Tiger Leaping Gorge station is located at the upstream entrance of the gorge, while the dam for the Liangjiaren station lies between the Upper Tiger Leaping Gorge and the Middle Tiger Leaping Gorge. [Marked on the map below in orange as Liangjiaren.]

To some extent, the Liangjiaren Station serves as a counter-regulation for the high dam and large reservoir at the Upper Tiger Leaping Gorge. Its primary purpose is to stabilize the substantial fluctuations in the outflow from the latter. Additionally, it operates as a diversion station, harnessing the significant elevation drop between the Upper and Lower Tiger Leaping Gorge. Water from the dam at Liangjiaren is diverted through tunnels to downstream power plants, where it is used for electricity generation.

“The interdependence between the Liangjiaren Hydropower Station and the Upper Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Station has resulted in construction delays for the Liangjiaren site, as progress on the Upper Tiger Leaping Gorge Station remains stalled. Moreover, in response to widespread opposition and public sensitivity surrounding the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project, hydropower developers have renamed the Upper Tiger Leaping Gorge Station ‘Longpan Hydropower Station,’ referencing Longpan Township in nearby Yulong Naxi Autonomous County.”

2. History of Opposition to the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project on the Jinsha River

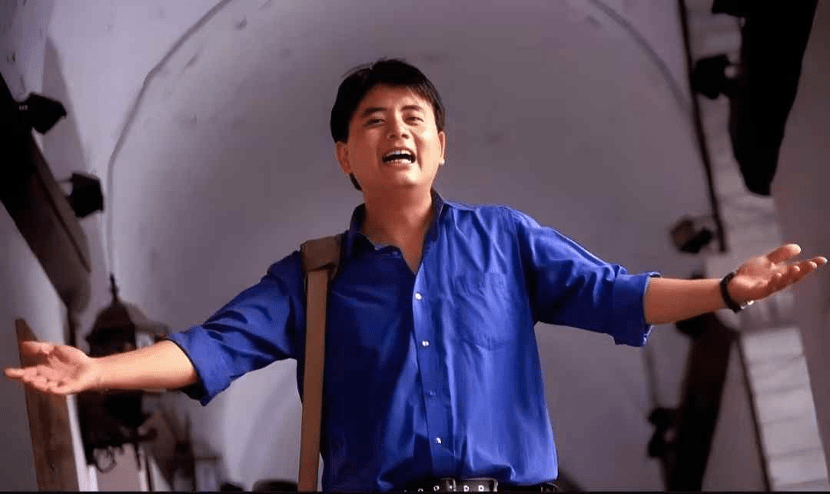

The Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project, which threatened to submerge the fertile river valleys of the Jinsha River, inevitably faced strong resistance from local residents. Among the most prominent figures in this opposition was Xiao Liangzhong, a young anthropologist from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Xiao, who was born in Chezhou Village in Jinjiang Town, Shangri-La City, grew up along the banks of the Jinsha River and became an advocate for protecting its unique cultural and ecological heritage.

In 2004, upon learning that the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project was set to proceed, which threatened to submerge his hometown, Chezhou Village, along with the fertile Jinsha River valleys and the renowned “First Bend of the Yangtze River” at Shigu, Xiao set into action. He began collecting information, traveling widely, and advocating for the cause. He educated villagers, drafted petitions, and invited media reporters to visit the Jinsha River to cover the story. In collaboration with scholars, journalists, and environmental volunteers, he initiated efforts to protect Tiger Leaping Gorge and the First Bend of the Yangtze River.

During this period, large-scale hydropower development in China were causing significant environmental and social issues, leading to conflicts in various regions. Projects on rivers such as the Nujiang, Jinsha, and Lancang in Yunnan, and the Minjiang and Dadu rivers in Sichuan, were drawing widespread attention for their detrimental impacts on natural and cultural heritage, ecological systems, and the rights of local communities.

In December 2004, I joined Xiao Liangzhong and a few friends on an expedition to the Nujiang River, where plans for large-scale hydropower development were underway. Unexpectedly, shortly after returning to Beijing, Xiao Liangzhong passed away from a sudden heart condition caused by overwork in the early hours of January 5, 2005, at the age of just 32.

When Xiao’s ashes were brought back to Chezhou Village and laid to rest by the Jinsha River, a large crowd gathered to pay their respects. Many wept uncontrollably during the funeral. Touched by his unwavering dedication, the villagers pooled their resources to erect a stone monument near his grave, bearing the inscription “Son of the Jinsha River.” Xiao Liangzhong’s tireless efforts to protect his homeland left an enduring spiritual legacy for the communities along the Jinsha.

“The Son of the Jinsha River.”

In Wuzhu Village, Jinjiang Town, Shangri-La City, local farmer Ge Quanxiao has become a leading voice against the construction of the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project. The village, home to over 4,000 residents, thrives on nearly 5,000 mu of fertile farmland handed down through generations.

Ge Quanxiao told reporters, “This is the most prosperous area in western Yunnan. We harvest rice and corn twice a year, yielding over 2,000 catties of grain per mu. Families also raise cattle and sheep, enjoying a comfortable, carefree life.” He emphasized, “We are not impoverished and have no desire to move.”

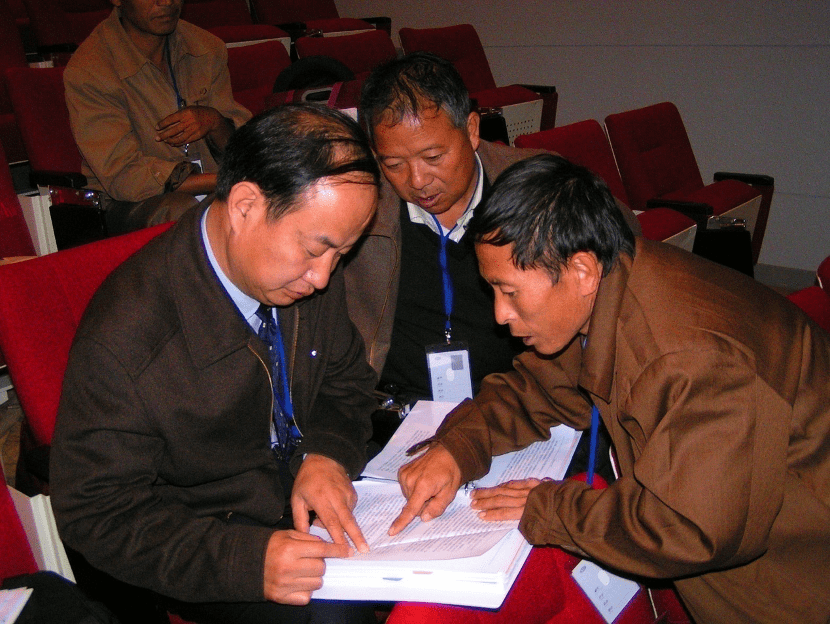

Ge Quanxiao not only united local residents to voice their concerns to the local government but also visited other hydropower stations in Yunnan that had already been built. There, he witnessed the impoverishment of many relocated communities, which deepened his understanding of the critical need for local minority peoples to participate in project decision-making and to actively defend their legitimate rights.

In October 2004, Ge Quanxiao, along with several other village representatives, attended the “United Nations Symposium on Hydropower and Sustainable Development” held in Beijing. At the conference, they presented a paper titled “Dam Construction and the Participation Rights of Local Minority Peoples.” This marked the first time that ethic minority representatives affected by hydropower projects in China directly addressed Chinese government officials, United Nations representatives, and domestic and international media at an international forum, articulating their interests and demands.

On March 13, 2006, over 10,000 residents living along the Jinsha River and impacted by the proposed Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project submitted a joint petition to then-Premier Wen Jiabao of the State Council. Titled Opinions on the Central Yunnan Water Diversion and Tiger Leaping Gorge High Dam, the petition voiced their collective desire to preserve the Tiger Leaping Gorge rather than develop it.

Just days after, on March 21, 2006, the hydropower company, without informing the local residents, began measuring houses and land in villages located in the inundation zone of the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project along the Jinsha River. This action, seemingly unreasonable, reflects a long-standing “routine” in China’s reservoir resettlement practices: property owners have no right to know about or participate in decisions regarding the disposal of their properties. Instead, the calculation and valuation of their assets are unilaterally conducted by the hydropower development authorities, who are the beneficiaries. The government then enforces demolition and relocation, leaving residents without a voice.

The hydropower company’s unauthorized surveying of houses and land, in their eagerness to begin construction, provoked the anger of local residents. On the same day, March 21, more than 10,000 people gathered in Jinjiang Town to stop the company’s actions. In response, the government of the Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan issued a public statement promising: “The government will not make a decision to build the hydropower station without the consent of the majority of people in the inundation zone. Please rest assured.” Following this, the Yunnan Provincial Resettlement Bureau and the Jinsha River Hydropower Development Company held a forum to apologize to the affected villagers along the Jinsha River.

As a result, the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project was effectively shelved. The government of the Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture even designated the area south of Tiger Leaping Gorge Town, on the left bank of the Jinsha River and within the inundation zone, as part of the Shangri-La Economic Development Zone in Diqing, Yunnan, for development and construction. This move signaled their decision to abandon the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project. In August 2010, the Yunnan Provincial Environmental Protection Department told reporters from the 21st Century Business Herald: “The Longpan and Liangjiaren hydropower stations will not be built.”

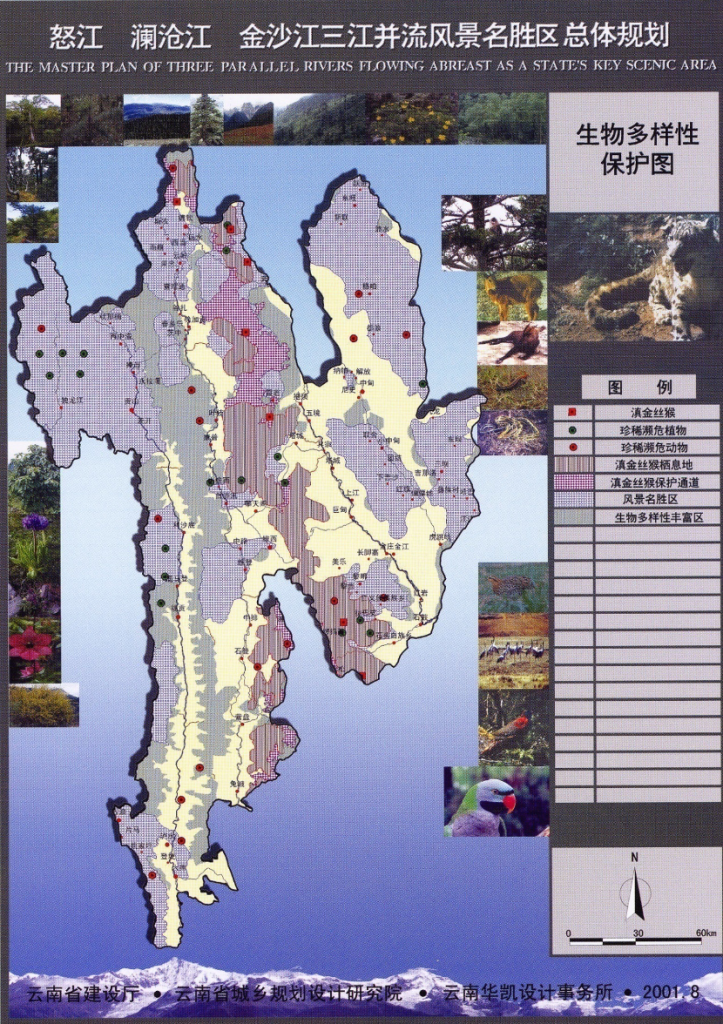

Of course, the potential impact of the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project extended beyond the immediate concerns of Jinsha River residents. Iconic natural landmarks such as the Tiger Leaping Gorge and the First Bend of the Yangtze River are not only critical components of the Three Parallel Rivers World Natural Heritage Site but are also national scenic areas and nature reserves. Any damage to these sites concerns the broader public interest. Since 2004, the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project has attracted significant attention from domestic experts, scholars, environmental organizations, and social media.

In September 2004, several grassroots environmental organizations, including Green Earth Volunteers, the Institute of Environment and Development, the Alashan SEE Ecological Association, Friends of Nature, Global Village of Beijing, Tianxiaxi, Community Action, the Global Environmental Institute, and Green Island, jointly issued a public appeal titled Save Tiger Leaping Gorge, Save the First Bend of the Yangtze River. The appeal called for an immediate halt to the imminent Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project.

From 2004 to 2005, the project became the focus of extensive media coverage, drawing widespread public attention and debate. Numerous prominent media outlets, including New Beijing News, China Youth Daily, Southern Weekend, South Wind Window, Xinmin Weekly, and China Central Television (CCTV), published a series of in-depth reports on the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project. These reports sparked widespread public attention and debate. Notable examples include Ma Jun’s article, A Dam to Be Built at Tiger Leaping Gorge: Destroying Scenic Beauty to Solve Central Yunnan’s Water Crisis?, published in Xinmin Weekly; Liu Jianqiang’s Tiger Leaping Gorge Emergency in Southern Weekend; The Uncertain Fate of Tiger Leaping Gorge by Xie Nian and Zhang Kejia in China Youth Daily; Where Is the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project Heading? by Yang Min in South Wind Window; and CCTV’s In Search of Shangri-La: Exploring the Disappearing River and Civilization, broadcast on the Focus program.

It can be said that the shelving of the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project was the result of joint efforts by local residents, grassroots environmental organizations, social media, and the general public. It also reflected the government’s willingness at the time to compromise and prioritize broader public interest and social stability over large-scale development initiatives.

3. Recent Developments in the Revival of the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project

Although the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project was previously shelved, the promise of substantial GDP growth, increased fiscal revenue, and lucrative investment returns continues to tempt local governments and hydropower developers who stand to benefit directly. This allure becomes even stronger during periods of economic downturn, financial difficulties for developers, or fiscal shortfalls for the government, fueling the impulse to prioritize profits over public and environmental interests.

In 2023, several experts aligned with China’s hydropower interest groups frequently published articles extolling the benefits of the Tiger Leaping Gorge reservoir as the lead project. These publications emphasized the project’s potential benefits and portrayed it as a leading initiative in the region’s hydropower development.

On April 8, 2024, the Yunnan Provincial Party Committee held a relocation mobilization meeting at the Diqing Prefecture government for the submerged area of the Longpan Hydropower Station. Township and village leaders from affected areas were instructed to organize meetings with village heads and team leaders to complete social stability risk assessment questionnaires. They were also urged to support the construction of the Longpan Hydropower Station.

In June 2024, villagers from a community along the Jinsha River convened a representative assembly and signed a Village Statement Opposing the Hasty Construction of the Longpan Hydropower Station on the Jinsha River. However, before the statement could be formally submitted, the villagers involved were subjected to daily visits by officials attempting to “convince” them to change their stance.

On September 13, 2024, the Yunnan provincial government issued a notice titled “Notice on Prohibiting New Construction Projects and Population Influx in the Land Acquisition and Submersion Area of the Longpan Hydropower Station Project in the Middle Reaches of the Jinsha River.” The notice stated: “All levels of government involved in land acquisition for the project must strengthen organizational leadership, earnestly carry out propaganda and explanations of immigration policies and regulations, conduct in-depth and meticulous public work, and take effective measures to ensure the smooth progress of resettlement work and promote the early construction and benefit realization of the project.” This so-called “reservoir sealing order” signals that Yunnan Province intends to officially restart the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project and marks the beginning of preliminary preparations.1

The areas designated under this reservoir sealing order span multiple regions:

- Yulong Naxi Autonomous County, Lijiang City: 17 villages in Shigu Town, Judian Town, Shitou Township, Liming Township, Tacheng Township, Daju Township, Jiukou Township, and Longpan Township.

- Shangri-La City, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture: 15 villages in Hutiaoxia Town, Jinjiang Town, Shangjiang Township, Nixi Township, Wujing Township, Shangri-La Industrial Park, and the Hutiaoxia and Wujing branches of the Shangri-La State-owned Forest Farm.

- Deqin County: One neighborhood committee and two villages in Benzilan Town, and eight villages in Tuoding Township and Xiaruo Township.

- Weixi Lisu Autonomous County: Three villages in Tacheng Town.

However, the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project remains unapproved by relevant central authorities. Neither the “14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) for a Modern Energy System” nor the “14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) for Renewable Energy Development” issued by the State Council included the Longpan (Tiger Leaping Gorge) Hydropower Station in the construction agenda. It was only referenced in the “14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) for a Modern Energy System” that “preliminary demonstrations of hydropower stations such as Longpan should be carried out in-depth.” Even if it were included in the national energy construction plan, prior to construction approval, a series of tasks such as environmental impact assessments, geological hazard risk assessments, and seismic safety evaluations need to be conducted, along with approvals from relevant central departments. Therefore, issuance of the reservoir sealing order by Yunnan Province for the Longpan Hydropower Station appears to be premature and somewhat suggests starting construction before approval, which does not conform to the standard procedures for large-scale engineering construction.

Furthermore, promoting the construction of the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project not only violates the local government’s previous commitment to shelving the project but also conflicts with the Yunnan Provincial Government’s May 2024 approval of the Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture Overall Plan (2021-2035). The approval explicitly emphasizes: “Strengthen the protection and management of critical ecological spaces such as the Jinsha River Basin Ecological Belt and the Diqing-Lijiang Biodiversity Corridor and stabilize the agricultural spatial structure of the major grain-producing areas along the Jinsha River.” If the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project is implemented, it would destroy these essential ecological belts and biodiversity corridors, while also dismantling the agricultural spatial structure of the grain-producing areas along the Jinsha River.

4. The Four Major Hazards of the Jinsha River Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project

4.1 Location in a Highly Active Fault Zone, Posing Severe Risks of Earthquakes and Landslides

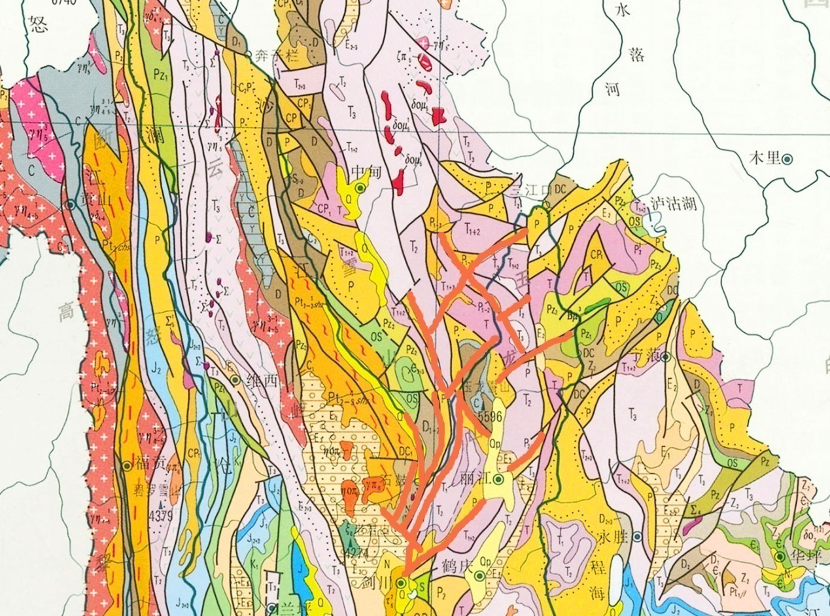

The Jinsha River does not continue flowing southward alongside the Lancang and Nu Rivers, part of the Three Parallel Rivers system. Instead, it makes a nearly 180-degree turn near Shigu and abruptly flows northward. This phenomenon is not coincidental but is due to this region being the most tectonically active along the entire Jinsha River.

This intense tectonic activity has resulted in the formation of towering peaks such as Yulong Snow Mountain (5,596 meters) and Haba Snow Mountain (5,396 meters), home to the southernmost modern glaciers in the Northern Hemisphere. Additionally, the region is traversed by a massive northeast-trending fault zone, which has guided the Jinsha River’s path. The river has carved its way through this fault between Yulong Snow Mountain and Haba Snow Mountain, creating one of the world’s most extraordinary gorges.

Due to its unique geological characteristics, the Tiger Leaping Gorge region is the most tectonically active and earthquake-prone area along the Jinsha River. It is also a hotspot for gravitational geological hazards, such as collapses and landslides.

The gorge features exceptionally steep valley walls, with intense physical weathering. Under the combined effects of torrential rains and seismic activity, the slopes are highly unstable, making them prone to various forms of material flow. The Tiger Leaping Stone, located in the middle of the river at Upper Tiger Leaping Gorge, is a massive boulder left behind by a past mountain collapse.

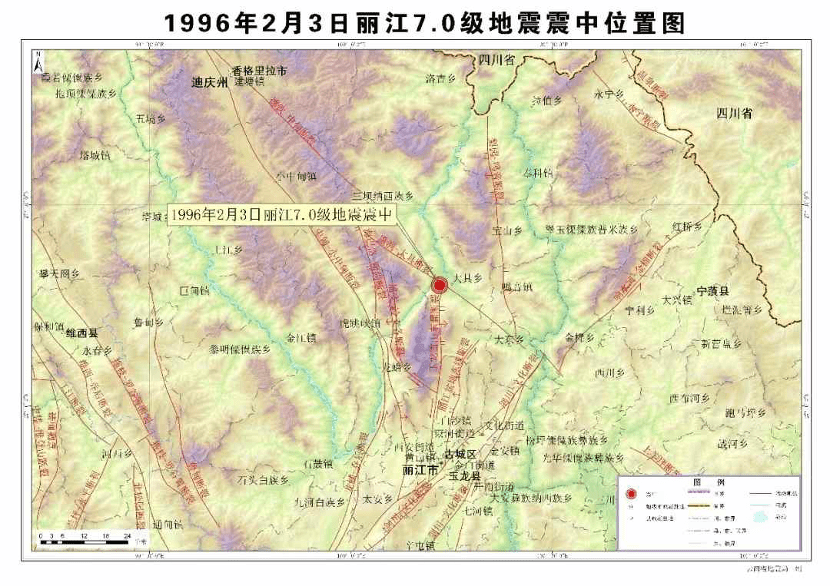

According to records, the northeast-oriented fault zone surrounding the Tiger Leaping Gorge has experienced seven earthquakes of magnitude 6.0 or higher over the past 500 years, with seismic intensities often exceeding level 8. These significant seismic events include:

July 24, 1481: Jianchuan earthquake, magnitude 6.25

June 27, 1515: Northwest Yongsheng earthquake, magnitude 7.75

June 16, 1688: Jianchuan earthquake, magnitude 6.25

May 25, 1751: Jianchuan earthquake, magnitude 6.75

October 17, 1925: Northwest Lijiang earthquake, magnitude 6.0

December 21, 1951: Lijiang earthquake, magnitude 6.3

February 3, 1996: Lijiang earthquake, magnitude 7.0

Notably, the most recent significant earthquake, the 7.0-magnitude Lijiang earthquake on February 3, 1996, had its epicenter near the lower gorge’s exit at Tiger Leaping Gorge. This earthquake caused massive collapses and landslides, which temporarily blocked the river at the lower gorge’s outlet.

Under such geological conditions, constructing a high dam at Tiger Leaping Gorge would require extensive excavation of the mountain slopes and riverbed, leading to significant alterations in the surface topography. This large-scale disturbance could easily lead to slope instability, surface soil and rock detachment, and the accumulation of excavation debris, which, in turn, could trigger collapses, landslides, and debris flows.

Given that the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project involves an exceptionally large dam and reservoir built on an active fault zone, the immense static pressure of the reservoir water on the fault zone and the pore pressure generated by water seeping into the faults could potentially induce earthquakes, including major ones.

Moreover, after the project’s completion, reservoir-induced erosion of the banks, prolonged water saturation, and significant fluctuations in water levels could exacerbate the instability and reactivation of geological hazards in this already disaster-prone region.

Even if the Tiger Leaping Gorge dam is constructed to meet seismic design standards, the dam itself may not suffer direct damage during an earthquake. However, the occurrence of large-scale landslides or rockfalls triggered by a major earthquake or other factors could pose significant risks of dam destruction, dam breach, and reservoir water overflow.

According to national Regulations on the Prevention and Control of Geological Disasters, geological environment protection zones must be established in areas at risk of disasters that could impact regional or national security. Activities such as blasting, slope cutting, and construction, which may trigger geological disasters, are strictly prohibited within these zones. From the perspective of disaster prevention and mitigation, the implementation of the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project is inadvisable.2

4.2 Destruction of Natural Wonders, Ecosystems, and Cultural Heritage within the Three Parallel Rivers World Natural Heritage Site, National Scenic Areas, and Nature Reserves, Including Tiger Leaping Gorge and the First Bend of the Yangtze at Shigu

Tiger Leaping Gorge, the First Bend of the Yangtze River at Shigu, the Jinsha River’s broad valley (Longpan-Tacheng), and the surrounding mountain ranges lie in the transition zone from the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau to the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau. This region is renowned for its breathtaking landscapes and extraordinary natural features.

The sources of the Jinsha River, such as the Tongtian and Tuotuo Rivers on the northern slopes of the Tanggula Mountains, along with the snow-capped peaks of the Haba and Yulong Snow Mountains flanking Tiger Leaping Gorge, are part of the southern extension of the Shaluli Mountains in the western Sichuan Plateau. On the right bank of the Jinsha River valley, west of Shigu, lies the Yunling Mountain range, a southern extension of the Tanggula-Ningjing Mountains.

Furthermore, this region, characterized by the parallel flows of the Jinsha, Lancang (Mekong), and Nu (Salween) rivers forming the towering mountains and deep gorges of the Hengduan Range, has long been an internationally acclaimed destination of natural and cultural significance.

Within the Three Parallel Rivers World Heritage Site, areas directly or indirectly impacted include the Haba Snow Mountain area on the left bank of Tiger Leaping Gorge, the Qianhu Mountain area on the left bank of the Jinsha River’s broad valley, and the Laojun Mountain and southern section of the Baima-Meili Snow Mountain areas on the right bank. These encompass portions of the Three Parallel Rivers National Scenic Area, the Laojun Mountain National Scenic Area, the Laojun Mountain National Geopark, the Haba Snow Mountain Nature Reserve, as well as numerous biodiversity hotspots and the critical habitat of the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey in Yulong and Laojun Mountains.

On the right bank of Tiger Leaping Gorge and the right bank of the First Bend of the Yangtze River, affected areas include Yulong Snow Mountain National Scenic Area’s first- and second-level protected zones, such as Yulong Snow Mountain, Tiger Leaping Gorge, and Shigu Town. Additionally, this region contains the Yulong Snow Mountain National Nature Reserve, Yulong Snow Mountain Glacier National Geopark, Yulong Snow Mountain National Forest Park, essential habitats for mammals, birds, and insects, as well as several biodiversity hotspots.

Tiger Leaping Gorge and the First Bend of the Yangtze River at Shigu are world-renowned natural wonders. The construction of the Longpan Dam at Upper Tiger Leaping Gorge and the Liangjiaren Dam will directly destroy the gorge’s natural landscape, fundamentally altering its unique geological and geomorphological structure of immense value. Furthermore, the reservoirs created by these dams and the diversion of most river water through hydroelectric tunnels will completely transform the roaring rapids of Tiger Leaping Gorge. What is now a powerful torrent will either become a stagnant artificial lake or a diminished trickle. The massive reservoir formed by the Longpan Dam will submerge much of the First Bend of the Yangtze River and Shigu Town, permanently burying these critical components of the World Heritage Site and the National Scenic Area beneath the water.

Shigu, where the river widens and slows, is ideal for ferry crossings and has historically been a strategic military site. Zhuge Liang’s May crossing of the Lu River, Kublai Khan’s leather raft crossing, and the Red Army’s northward march to Ganzi all passed through here. Shigu, a key part of the national scenic area, features historical and cultural landmarks such as the Ming-era drum-shaped stone tablet (from which the town gets its name), the Qing-era Tiehong Bridge, traditional residences, the Long March crossing memorial, and the Red Army River Crossing Memorial Hall.

The Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project threatens significant biodiversity hotspots and ecological function zones within the Three Parallel Rivers World Heritage Area, as well as the Yulong Snow Mountain Nature Reserve, which lies beyond the heritage boundary. Due to the dramatic altitude variation from river valleys to mountain peaks, the region features a complete vertical spectrum of vegetation and climate zones, ranging from subtropical to cold temperate. Key conservation targets in these areas include mountain mixed-forest ecosystems, rare and endangered flora and fauna, pristine vertical climate and vegetation gradients, dense high-altitude lakes and wetlands, glaciers, and their remnants.

Both construction activities and reservoir operations pose significant risks to these ecosystems and habitats, not only within the dam and reservoir zones but also in the surrounding areas. These activities will intensify the fragmentation of ecological corridors and biodiversity zones. The vast size and water storage capacity of the reservoir could also alter the local climate, potentially destabilizing the glaciers on Yulong and Haba Snow Mountains.

The project would eliminate the last remaining natural stretch of the middle and lower Jinsha River (from the tail of the Liyuan reservoir to Benzilan), destroying critical habitats for many unique and endangered fish species native to the river, thereby driving them to the brink of extinction.

Additionally, the large-scale relocation of residents from the submerged areas to nearby regions will further encroach upon and disrupt adjacent nature reserves, biodiversity hotspots, and ecological function zones due to housing construction, road building, land clearing, and deforestation in areas already constrained by limited land resources.

The impacted areas are home to a multicultural mosaic of Naxi, Lisu, Bai, Tibetan, Yi, Miao, and Han communities, reflecting the rare cultural diversity and the distinctive socio-cultural structure of northwest Yunnan. Rich intangible cultural heritage coexists with numerous tangible historical relics, such as ancient towns, villages, architecture from the Ming Dynasty, ancient tombs, rock paintings, and inscriptions.

The construction of the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project would fragment these indigenous communities, dismantling their unique cultural and social structures. Moreover, it would submerge and irreversibly destroy a significant portion of the historical artifacts and cultural sites tied to the region’s diverse heritage.

4.3 Submerging the Fertile Basin from Longpan to Tacheng Along the Jinsha River, Forcing the Relocation of Over 150,000 Residents, and Threatening Regional Social Stability

The Longpan Reservoir of the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project would completely submerge the largest basin along the Jinsha River. This area, a crucial grain-producing region and agricultural hub in northwest Yunnan, benefits from the region’s most favorable soil and climatic conditions. The inundation would engulf approximately 200,000 mu of farmland, as well as a significant number of orchards and forested areas. Thanks to its exceptional natural resources, local farmers in this area have historically enjoyed relatively high living standards.

For decades, reservoir-induced relocation in China has placed displaced residents in a position of passivity and compulsion, leaving them unable to participate in decision-making processes or influence the fate of their homes, land, and other properties. This lack of agency prevents them from safeguarding their legal rights. Many have been forcibly moved from fertile and prosperous river valleys to barren slopes or mountainous areas, losing access to high-quality living and production environments and consequently falling into poverty.

In the multiethnic communities of northwest Yunnan, which the Tiger Leaping Gorge project affects, such devastation of the indigenous population’s fertile land and cherished homes would severely undermine ethnic unity and disrupt the region’s social stability.

4.4 Undermining the Central Committee’s Strategy of “Preserving Rather Than Overdeveloping the Yangtze River” and Contradicting the Global Trend of Sustainable Development

Since the 21st century, large-scale hydropower development in China has adopted a model of exhaustive exploitation, transforming many free-flowing rivers into interlinked reservoirs through comprehensive cascade development across entire rivers and basins. As a result, many of China’s once free-flowing rivers have been transformed into a series of interlinked reservoirs.

The widespread loss of natural rivers—essential for sustaining aquatic biodiversity, natural landscapes, and human living environments—has brought the ecological and water environments of China’s rivers to a critical juncture. This destructive approach runs counter to the Chinese government’s declared strategy of prioritizing ecological conservation over reckless development, particularly in the Yangtze River Basin. It also starkly contrasts with the global movement toward sustainable development and environmental protection.

The Central Committee and the central government are fully aware of this crisis and have thus proposed strategic decisions such as “Preserving Rather Than Overdeveloping the Yangtze River.” This represents a critical choice in response to the devastated state of China’s rivers: should the focus be on unsustainable, exploitative development, or on harmonious coexistence between humans and nature through sustainable development?

The UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, adopted on November 16, 1972, mandates that “Any property included in the World Heritage List must be strictly protected by its respective state under applicable laws,” and that “States Parties must not deliberately take any action that might directly or indirectly damage cultural and natural heritage within their territory.”

The areas affected by the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project—including World Natural Heritage sites, national nature reserves, national scenic spots, national geoparks, and national forest parks—are explicitly designated by the Chinese government as “prohibited development zones.” National laws and regulations clearly stipulate that construction activities unrelated to nature conservation, scientific research, or tourism are forbidden in these areas.

Agricultural production bases like the Jinsha River Wide Valley are also designated as “restricted development zones” by the state. These are key agricultural areas with abundant farmland and favorable conditions for agricultural development.

As outlined above, the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project is incompatible with legal standards, national policies, public interest, and the rights of local residents. The ability to preserve the last natural stretch of the Jinsha River’s middle and lower reaches, to protect its precious natural and cultural heritage, and to safeguard the beautiful homeland along the Jinsha River, represents the ultimate test for the nation. Let us hope that what remains is a legacy of honor, not a monument to shame.

1 The issuance of this “Notice” can be seen as a prelude to the beginning of the hydropower project. Following the previous suspension of the Tiger Leaping Gorge (Longpan) Hydropower Station, the hydropower company (along with the local government) was left dissatisfied with the setback and worked behind the scenes to push the project forward. Moreover, given the generally long construction timelines of dams, many projects, including the Three Gorges Dam, have encountered individuals from outside of the submersion zones seizing on the opportunity to build houses within the area, even investing in unrelated projects. Similarly, non-relocated residents sometimes move into the area, all with the aim of securing resettlement compensation. To prevent such situations, hydropower companies and local governments usually issue “Notices” to close off the area beforehand. Without such measures or “closure orders” (such as a reservoir sealing order), unauthorized construction or population migration into the area may continue, leaving the hydropower station developers responsible for relocation and resettlement compensation, which significantly increases the overall cost.

2 See Regulations on the Prevention and Control of Geological Disasters. Chapter 3: “Geological Disaster Prevention Article 19.” For areas and locations where signs of geological disasters have been detected and where there is a possibility of causing casualties or significant property damage, the county-level people’s government shall promptly designate such areas as geological disaster risk zones, make a public announcement, and set up clear warning signs at the boundaries of the geological disaster risk zones. Within geological disaster risk zones, activities such as blasting, slope cutting, construction projects, and other activities that may trigger geological disasters are prohibited. Governments at or above the county level shall organize relevant departments to promptly implement engineering management or relocation and avoidance measures to ensure the safety of residents’ lives and property within geological disaster risk zones.

Historical Documents

- Lao Xia, Xiao Liangzhong, Northwestern Yunnan Civilization: Being Unveiled and Destined for Destruction, Guangming Daily Network, 2004-07-07.

- Ma Jun, Tiger Leaping Gorge Set to Be Dammed: Ruining Scenic Beauty to Solve Central Yunnan’s Water Crisis?, Xinmin Weekly, 2004-09-06.

- Guo Xiaojun, NGOs Urge Halt to Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Project, New Beijing News, 2004-09-27.

- Liu Jianqiang, Tiger Leaping Gorge Emergency, Southern Weekly, 2004-09-29.

- Peng Xingting, Reflecting on the “Developmentalism Myth” from Tiger Leaping Gorge, China Youth Daily: Ice Point Commentary, 2004-09-29.

- Xie Nian, Zhang Kejia, Tiger Leaping Gorge’s Uncertain Fate, China Youth Daily, 2004-09-30.

- Yang Min, The Future of Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Station, South Reviews, 2004, Issue 10 (Upper), pp. 46-50.

- Jiang Wei, You Are Changing History, China Youth Daily, 2004-12-15.

- CCTV, In Search of Shangri-La: Exploring a Disappearing River and Civilization, Focus Report, 2005-04-09.

- Wang Hui, Son of the Jinsha River—In Memory of Xiao Liangzhong, Aisixiang Network, 2005-06-14.

- Fan Xiao, Impacts of Hydropower Development on World Heritage Sites and National Scenic Areas—Focusing on Southwest China, Chinese Landscape Architecture, 2007-10.

- Dai Qifu, Xiao Liangzhong: Guardian of the Jinsha River, Folklore Blog, 2009-04-01.

- Wen Jing, Peng Haixing, “Resurrection” of Hydropower Stations: Comprehensive “Unblocking” of Jinsha River’s Middle Reaches? Disputes Remain over Longpan and Liangjiaren Projects, 21st Century Business Herald, 2010-08-24.

- CCTV, Witness: The Guardians of Shangri-La, Chronicles Column, 2012-05-20.

- Yang Hongjun, Son of the Jinsha River—In Memory of Anthropologist Xiao Liangzhong, China Writers Network, 2012-09-18.

- Liu Jianqiang, The Insurmountable Tiger Leaping Gorge, Dialogue with Earth Network, 2013-04-19.

The cover image for the foreword was created by generative AI.

This report is available for download below as a PDF file:

Categories: China's Dams, Dams and Earthquakes, Dams and Landslides, Earthquake, Three Gorges Probe

1 reply »