A transboundary super dam proposed for occupied Tibet, near its border with India, poses significant concerns and risks. A report by Chinese geologist Fan Xiao delves into the infeasibility of the massive development, revealing it isn’t even needed.

As part of China’s long-range objectives to create a modern energy system, the country’s hydropower lobbyists have their sights set on the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo, the fifth longest river in China and the largest river in Tibet Autonomous Region. The construction of a proposed super dam (the world’s largest if built) on a transboundary river in a seismically active region carries significant risks and the potential for unprecedented costs. In addition to the concerns of Tibet and downstream nations, India and Bangladesh, analysts are voicing their alarm over the project’s environmental and geopolitical dangers.

Among them is renowned Chinese geologist and environmentalist, Fan Xiao, who breaks down what’s at stake in the following report translated by Probe International. He notes the dam is not needed “to reduce emissions” and cannot be justified as a climate change project. “In terms of Tibet’s own energy needs, there is no requirement” for a super dam in this area. Hydropower stations in China’s Sichuan and Yunnan provinces even have to release excess water due to lack of demand, he says. However, the allure of the “increased GDP, investment, and tax revenue” that such projects generate, says Fan, is a great temptation for governments and vested interest groups.

The Yarlung Tsangpo (its name in Tibet) is also known as the Brahmaputra, which flows through northeastern India and Bangladesh.

By Fan Xiao

Originally posted October 18, 2022 on the WeChat account “HeShanWuYan” (Rivers and Mountains in Silence; 河山无言)

The Hengduan Mountains and Southeastern Tibet region, which extends from the Tibetan Plateau to the Sichuan Basin, the Yunnan Plateau, and the Brahmaputra River plains in India, is the richest area in China in terms of hydropower resources.

Beginning in the 21st century, unprecedented large-scale cascade hydropower development has been carried out on the Min, Dadu, and Yalong rivers within Sichuan, as well as on the Jinsha and Lancan-Mekong rivers at the boundaries of Sichuan, Yunnan, and Tibet. This makes Sichuan and Yunnan the top two provinces in China for hydropower resources and the source of power for the “West-to-East Power Transmission” grid.

However, because the growth of hydropower capacity has exceeded the growth in demand for electricity, both Sichuan and Yunnan have increasingly resorted to “spilling” water – releasing water directly from reservoirs without passing it through power-generation equipment.1

Despite the surplus supply of hydropower, plans are underway to build still more hydropower projects on the Yarlung Tsangpo, Niyang, Yigong Tsangpo, and Palong Tsangpo rivers in Tibet. It is worth noting that Tibet itself does not have the significant demand for energy that would necessitate large-scale hydropower development on these rivers. In addition to a lack of demand for Tibetan hydropower both domestically and internationally, there are also high costs associated with its transmission.2

Furthermore, the cascade hydropower development of these rivers could result in significant ecological damage to the pristine and biodiverse environments of eastern and southeastern Tibet, often referred to as a genetic treasure trove of biodiversity.

This report discusses the infeasibility of the proposed massive hydropower development at the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo River from the perspective of geological and environmental risks.

The Yarlung Tsangpo and its Great Bend

The Yarlung Tsangpo River originates from the Jiemayangzong Glacier on the northern slope of the Himalayas in Pulan County, Tibet. It flows from west to east for approximately 1,600 kilometers through the parallel valleys of southern Tibet within the Himalayan Mountain range. After reaching the town of Paizhen in Milin County, it turns north and forms a horseshoe-shaped bend on the northern side of Mount Namcha Barwa, with an elevation of 7,787 meters on the right bank, and Mount Gyala Peri, and an elevation of 7,257 meters on the left bank. From here, it cuts through the Himalayan Mountain range, and then flows southward into the Brahmaputra River-Ganges Plain in South Asia.

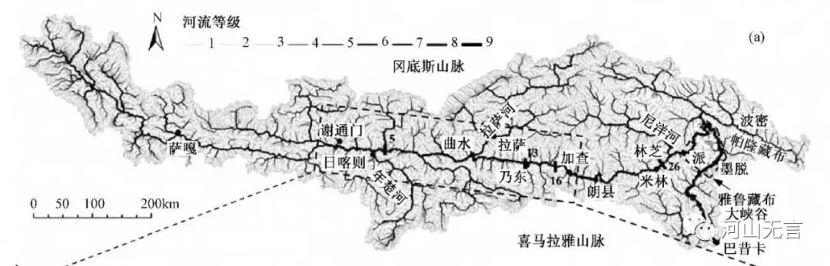

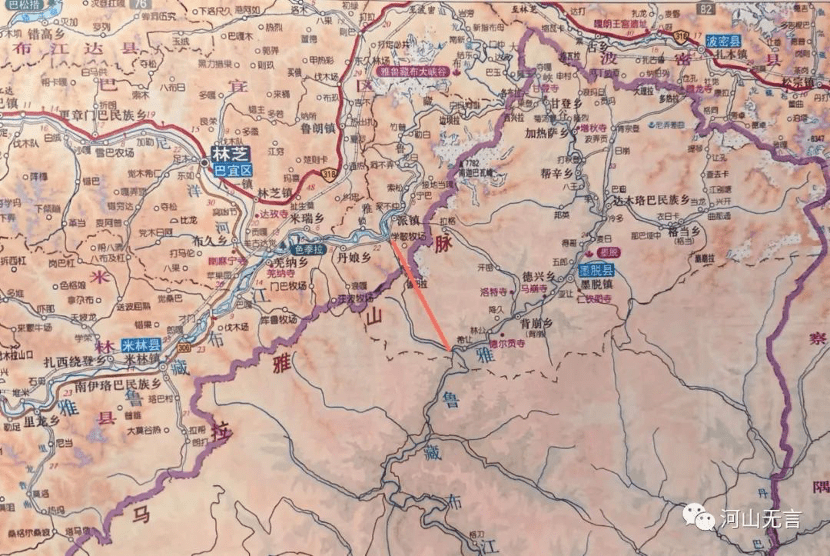

Figure 1: River network of the Yarlung Tsangpo River Basin (Credit to Wang Zhaoyin et al., 2014)

The Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo River, stretching from Paizhen Town in Milin County to Baxika Village in Motuo County, covers a length of 505 kilometers, with a maximum depth of 6,009 meters and an average depth of 2,268 meters. It is not only the world’s largest canyon but due to its passage through the Himalayas, serves as a critical water vapor and geographical corridor linking the Indian Ocean to the southeast of the Tibetan Plateau, as well as connecting the Tibetan Plateau to the South Asian subcontinent.

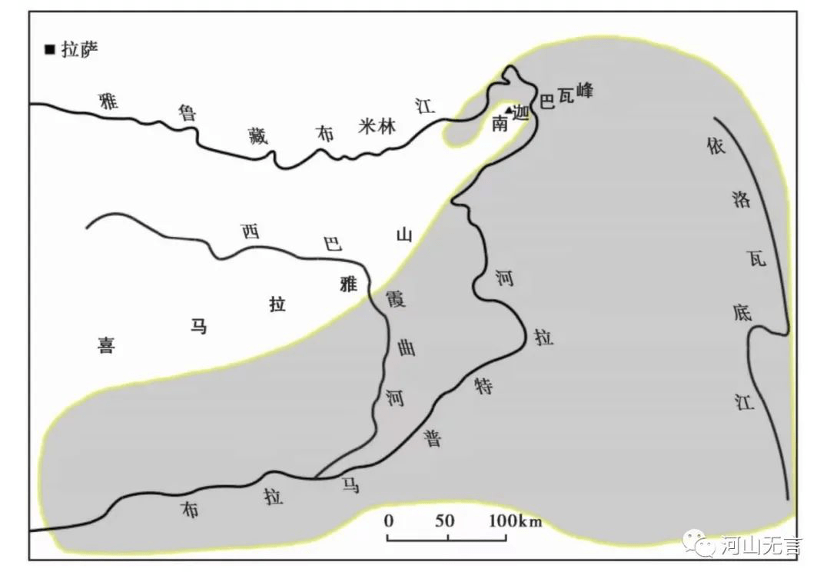

This unique geographic feature has created China’s largest marine glacial group in southeastern Tibet and serves as a significant meeting point for different biogeographic regions. It also encompasses China’s most complete mountain vertical natural zone, ranging from river valley subtropical monsoon forests to high-altitude alpine lichen ecosystems.

At an astounding vertical height of more than 7,000 meters on the southern slope of Mount Namcha Barwa, one can observe ecosystems and vegetation types resembling those found from the Equator to the North Pole. Due to the deep-cut canyon and strong warm, humid airflow from south to north, the tropical climate and natural zones of the Northern Hemisphere advance northward by approximately 6 degrees latitude in this region. This phenomenon extends to the northernmost boundary at approximately 29°30′ north latitude, with elevations reaching around 1,100 meters, making it the highest limit of tropical vertical distribution in the Northern Hemisphere.

Figure 2: Indian Ocean tropical monsoon climate distribution region (Source: Chao Xie et al., 2017)

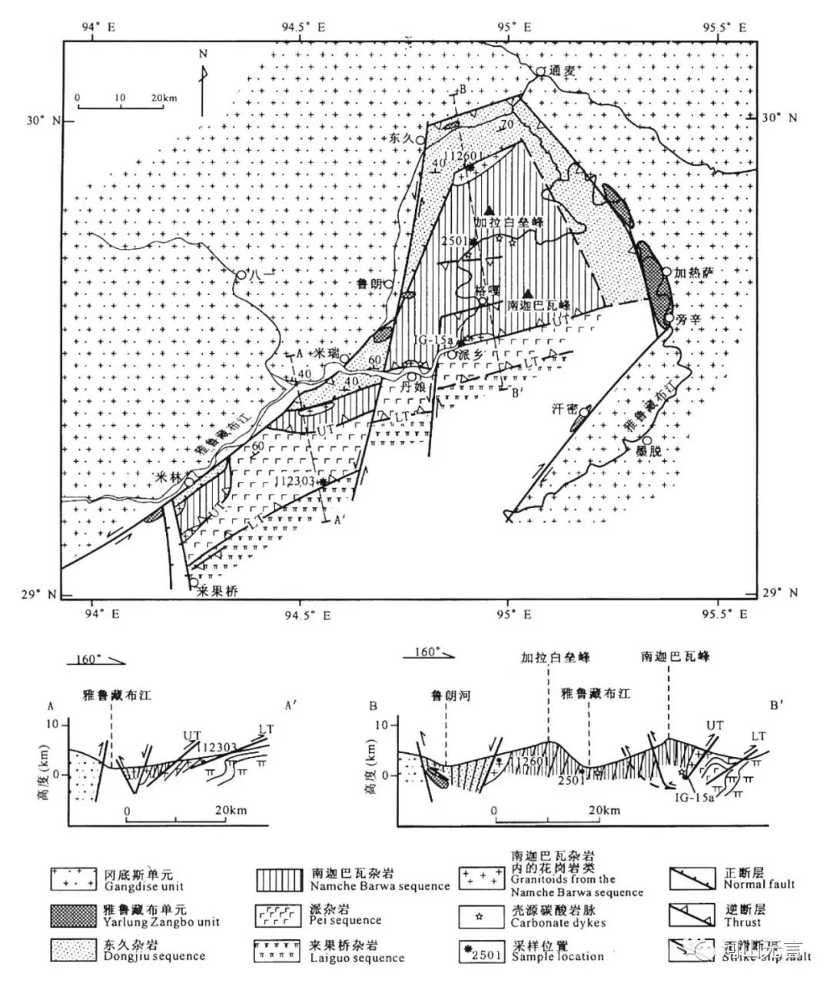

The formation of the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo River and its grand canyon is not accidental. It is the result of a collision between the Indian Plate and the Eurasian Plate at both ends of the Himalayan orogeny, which formed two wedged “corners” known as the eastern and western “syntaxis”3 or tectonic structures in geological terms: the most intensely deformed regions in the Himalayan orogeny.

It is the pushing and squeezing of these two “syntaxis” that created the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo River and the peak of Mount Namcha Barwa at the eastern end of the Himalayas, as well as the Indus River Bend and the peak of Nanga Parbat at the western end of the Himalayas. The Tibetan Plateau is squeezed and narrowed like a waist in proximity to these two tectonic structures, leading to significant changes in the orientation of mountain ranges, such as the Hengduan range in the east and the Hindu Kush range in the west. It also results in the closely interwoven landscape of mountains and gorges, such as the natural wonder of the confluence of three rivers at the boundary of Tibet, Sichuan, and Yunnan.

Figure 3: Location of the eastern “syntaxis” and the western “syntaxis” of the Himalayas (shown as white circles on the map).

It is precisely because of the existence of this eastern Himalayan “syntaxis” that the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend has become the region with the most intense tectonic uplift at the edge of the Tibetan Plateau, featuring well-developed faults, deep topographic incisions, frequent earthquakes, and a high susceptibility to mountain hazards, such as landslides and rock falls.

The Great Bend region is susceptible to geological events, especially earthquakes

The formation of the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend’s landscape is related to the occurrence of major faults that have experienced significant activity since the Late Cenozoic era.4 Specifically, the river segments on both the north and south sides of the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo, which run parallel to the Yarlung Tsangpo Fault (Milin-Mirui-Lulang-Dongjiu left-lateral strike-slip fault) and the Himalayan Central Thrust fault, developed due to these tectonic activities.

In addition, there are also faults that are nearly perpendicular to the Himalayan Mountain range, crossing near the apex of the Great Bend, the western side of Mount Namcha Barwa, and near the Doshong La Pass. These faults include the Jiali Fault, Motuo Fault, and Apalong Fault. These faults formed at least around seven-million years ago (Zhang Jinjiang et al., 2003). The reason for the formation of the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo River in this area is also related to the activity of the northwest-trending Jiali Fault.

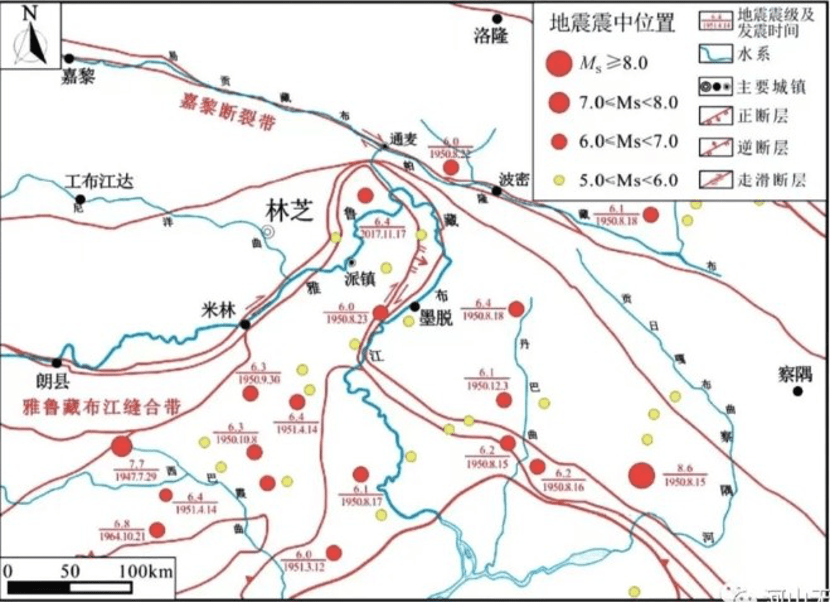

Figure 4: 1:1,000,000 geological map of the eastern “syntaxis” of the Himalayas (Source: Liu Yan et al., 2006)

Research suggests (Ding Lin et al., 1995) that due to intense tectonic movements, the uplift rate of the crust in the vicinity of the Great Bend reached 5 to 10 millimeters per year for approximately one million years. About three-million years ago, the average elevation in this area was around 1,100 meters, and by ~500,000 years ago, the average elevation had risen to approximately 4,400 meters. Intense tectonic movements and fault activity are naturally accompanied by strong seismic activity. Although historical earthquake records are scarce due to the remote location, according to the “The Catalogue of Chinese Historical Strong Earthquakes from the 23rd century BC to 1911 AD”5, there were two recorded strong earthquakes in the Chayu area near the Great Bend prior to 1911: a 6.5-magnitude earthquake in December 1878 and another 6.5-magnitude earthquake in July 1911.

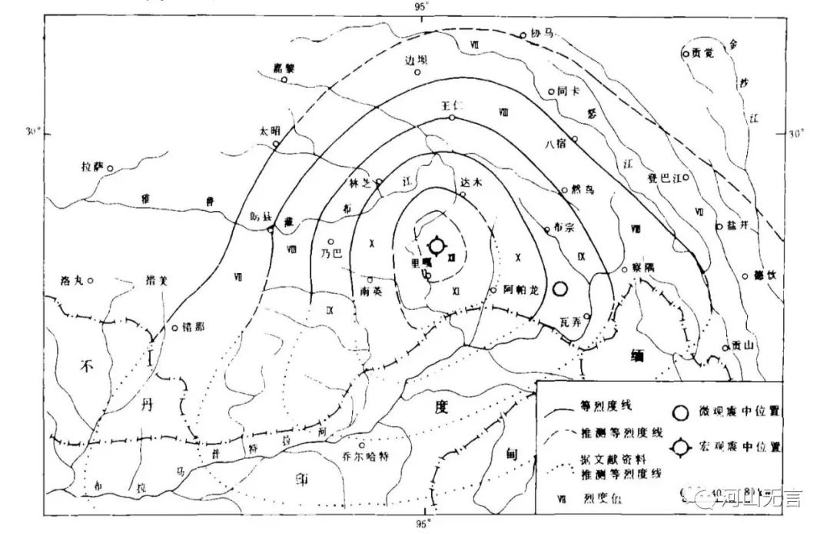

One of the most famous modern earthquakes associated with the eastern Himalayan tectonic structure is the magnitude 8.6 Chayu-Motuo earthquake that occurred on August 15, 1950. It is also one of the most renowned major earthquakes globally. The epicenter was located at approximately 28.4° north latitude and 96.7° east longitude. The most severely affected areas were in Motuo and Chayu, with the highest intensity level reaching XII.6 Buildings were completely destroyed, and despite the sparsely populated nature of the Great Bend region, around 1,800 people lost their lives.

Villages such as Yedong, Gelin, Beibeng, Zhibai, Didong, and Bibo were either swept into the Yarlung Tsangpo River along with landslides or buried by large landslide masses. Nine out of ten mountain cliffs collapsed, and numerous tributaries of the Yarlung Tsangpo River and its two banks experienced landslides that blocked the river. At least three locations along the main channel of the Yarlung Tsangpo River were blocked by collapsed landslide masses, leading to a temporary halt in the river’s flow.

The Chayu-Motuo earthquake also triggered large-scale avalanches and ice avalanches. The Zelongnong Glacier on the southern slope of Mount Namcha Barwa was fractured into six segments, leaping in sections along the valley. The terminal ice mass destroyed the village of Zhibai at the mouth of the valley, resulting in 97 casualties. The ice mass then plunged into the Yarlung Tsangpo River, creating an ice dam tens of meters high, which caused the river to be blocked for several hours.

The terminal end of the Zelong Glacier also shifted from its original elevation of 3,650 meters to 2,750 meters along the Yarlung Tsangpo River, with a horizontal displacement of 4.8 kilometers.

Figure 5: The Isoseismal Map of the 8.6 M Chayu-Motuo earthquake on August 15, 1950. Although the microscopic (instrumental) epicenter was near Lower Chayu, the macroscopic epicenter with the most severe surface damage, probably affected by the topography, was south of Xirang Village in Motuo County in the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend. (Source: You Zeli et al., 1991)

After the Chayu-Motuo earthquake of magnitude 8.6, frequent aftershocks continued for about a year. In the Great Bend region, there were 12 aftershocks with a magnitude of 6 or higher, with the highest aftershock reaching a magnitude of 6.4. The seismic damage caused by the earthquake exacerbated the occurrence of geological hazards such as collapses, landslides, and debris flow in this region for an extended period.

For example, the large landslide in the Jiamaqiming Gully, from Sotong to Tongmai in Bomi County, remained active for an extended period. Guxiang Gully in Bomi County experienced large-scale debris flows7 in 1953, which continued for more than half a century, with over 6,000 recorded occurrences. The accumulated debris at the mouth of Guxiang Gully reached approximately 100 million cubic meters and blocked the Palong Tsangpo River, forming Guxiang Lake. In September 1969, the Zelongnong Glacier surged again, rushing into the Yarlung Tsangpo River where it formed a tens-of-meters-high ice dam, which was breached the following day.

Following the Chayu-Motuo earthquake of magnitude 8.6, this region has experienced strong earthquakes with a magnitude of 6 or higher in the past ten years, including a magnitude 6.9 earthquake in Milin on November 18, 2017, and a magnitude 6.3 earthquake in Motuo on April 24, 2019.

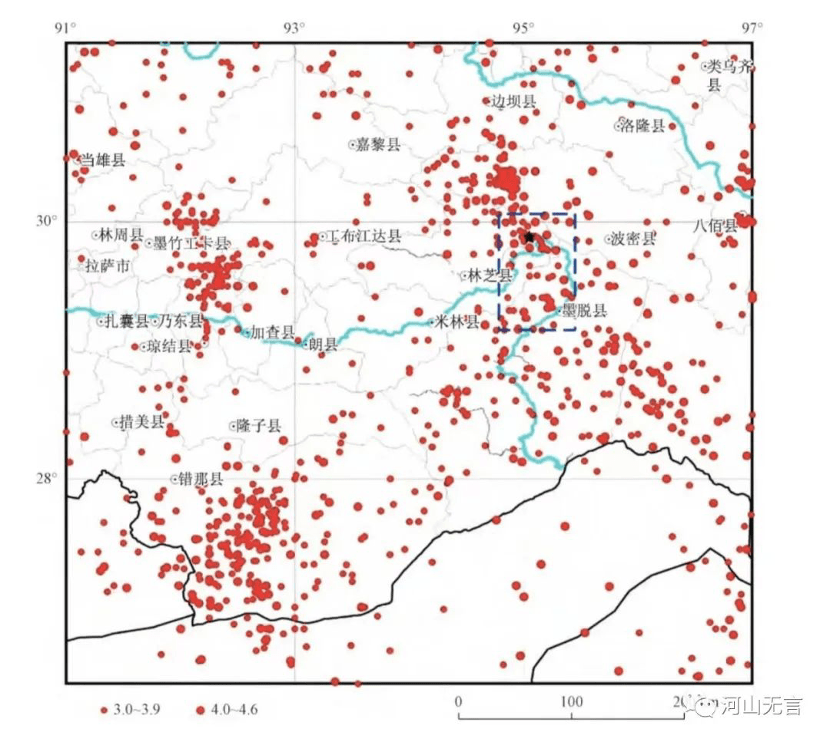

Figure 6: Distribution of earthquakes ≥5.0 M in the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend region in the last 70 years (Source: Li Bin et al., 2020)

Figure 7: Distribution of destructive earthquakes in the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend and surrounding areas from 1970 to 2016 (small red circle: magnitude ≥3.0-3.9; large red circle: magnitude ≥4.0-4.6) (Source: Zou Zinan et al., 2019)

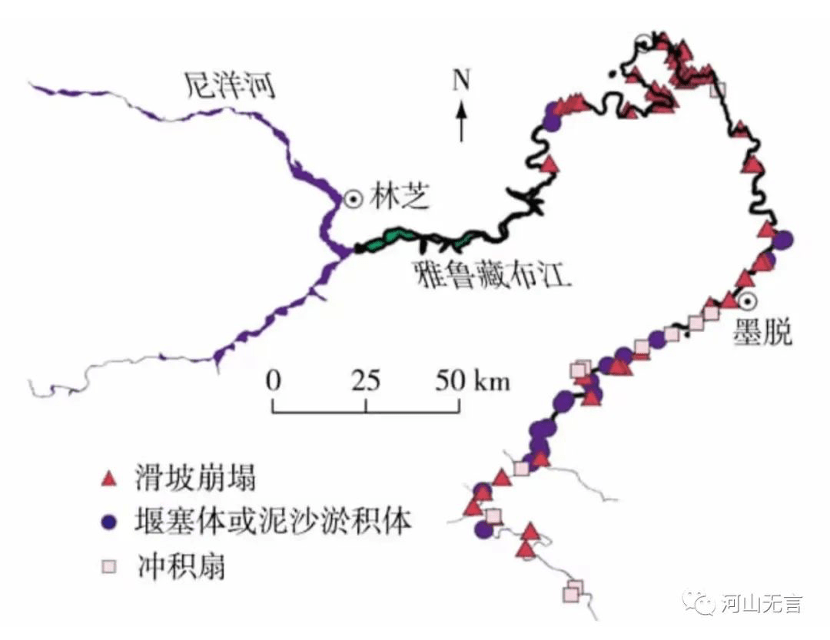

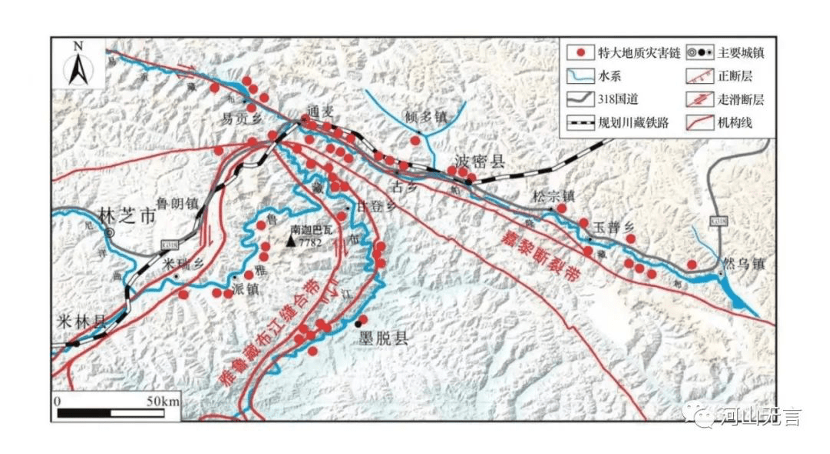

Due to tectonic uplift, river incision, seismic activity, and gravitational forces, a number of mountains on both sides of the Great Bend are in an unstable state, prone to collapse and landslides. According to some research findings (Zou Zinan et al., 2019), there are 108 major landslide masses within a certain range on both sides of the river from Jiala in Milin County to Xirang in Motuo County. The largest of these giant landslide masses had a volume of up to 4.5 million cubic meters.

Furthermore, according to surveys (Li Xiang, 2019), in the section of the Great Bend from Jiaresa Township in Motuo County to Xirang, there are 43 large-scale landslides. The largest of these, the Motuo landslide on the left bank of the Yarlung Tsangpo River, has a volume of up to 25.6 million cubic meters.

Figure 8: Distribution of risk points of mega-geological hazard chain in the Yarlung Zangbo River Great Bend area (the red triangle: landslides & collapses; blue circle: debris barrier or sediment accumulation; pink square: alluvial fan) (Source: Li Bin et al., 2020)

Figure 9: Distribution of the sites of landslides & collapses in the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend (the red triangle: landslides & collapses; blue circle: debris barrier or sediment accumulation; pink square: alluvial fan. Source: Yu Guoan et al., 2012)

Unprecedented costs and risks of building a giant hydro dam in the Great Bend

According to the proposed design, a high dam will be built near Paizhen Town of Milin County to hold back the Yarlung Tsangpo River, where a group of three giant tunnels, each with a diameter of 13 meters and a length of 34 kilometers will go through and beneath the Himalayas, forcing the river water to flow through the three giant tunnels rather than the big bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo River, and using the 2,400 meters of hydraulic drop after straightening the bend to generate electricity. At the lower end of the tunnels, a cascade of six dams will be built along the Xirang Qu, a tributary on the right bank of the Yarlung Tsangpo River, northwest of Xirang Village in Motou County. Once completed, the Motuo Power Station will have a total installed capacity of 43.8 million kilowatts8, thus becoming the world’s largest super-giant hydropower station.

Figure 10: The red line indicates the location of the giant hydropower development in the Grand Canyon of the Yarlung Tsangpo, upstream of the bend of the river. The dam will effectively cut-off the flow of water and divert it from Point A (Paizhen Town on the upstream) through three giant pipes to Point B (Xirang Village downstream). Once the high dam near Point A is completed, the water flow in the bend will be much less. In other words, the flow between Point A and Point B in the bend will be totally regulated by the high dam. Not surprisingly, the construction of high dams will completely alter the riverine conditions of the bend, especially the hydrological conditions.

In an area with such high geological risks, the construction of a mega-project like the one in the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend carries several potential hazards:

- Massive engineering excavation: building high dams, constructing giant tunnels, and developing a large-scale cascade of power stations in this region requires extensive excavation work. This massive alteration of the terrain can lead to the formation of steep cliffs and overhanging faces, which can exacerbate slope instability and increase the risk of landslides and collapses.

- Accumulation of excavated material: the excavation of large tunnels generates a significant amount of discarded material and debris. Disposing of this material in the narrow and steep terrain of the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend or nearby river valleys can significantly increase the risk of landslides, debris flows, and erosion.

- Due to the project’s location in a seismically active area, strong earthquakes can directly damage the project. If the project’s design takes into account seismic resistance, the dam structure itself may be able to withstand the destructive effects of strong earthquakes. However, earthquakes often trigger other uncontrollable events such as riverbank collapses, landslides, and mudslides, which can pose a significant threat to the project structure and may lead to severe secondary disasters.

- The high dam and large reservoir that will store water near Paizhen Town poses a high risk of inducing strong earthquakes due to their immense storage capacity, significant water level fluctuations, and their location on the active major fault line of the Yarlung Tsangpo River. Additionally, the original presence of many existing or potential landslides and rockslide bodies on both sides of the Great Bend could be further destabilized or reactivated by the inundation of reservoir water, erosion of reservoir banks, and the repeated changes in reservoir water levels. All of these factors may exacerbate the occurrence of geological hazards in the reservoir area9.

- The high dam and large reservoir’s interception of sediment, leading to sediment deposition, is another significant hazard. While the Yarlung Tsangpo River is relatively low in sediment content compared to other major rivers in China, the increased soil erosion along its banks in recent years has led to a trend of rising sediment load. Furthermore, research indicates that the middle reaches of the Yarlung Tsangpo River, from Lizhi in Zhongba County to Paizhen in Milin County, feature a wide valley where sediment accumulation can be as high as 900 billion cubic meters (Li Zhiwei et al., 2015). This stretch of the main river accepts sediment from tributaries including the Nianchu River, Lhasa River, and Niyang River. According to observations from the Nuxia Hydrological Station near the entrance of the great canyon, the Yarlung Tsangpo River carries an annual suspended sediment load (primarily fine sand) of approximately 30 million tons (Wang Zhaoyin et al., 2014). On the other hand, sediment generated in the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend area accounts for 50% of the sediment discharge into the Brahmaputra River (Yu Guoan et al., 2012).

Therefore, the construction of a big dam in the Great Bend would lead to rapid reservoir sedimentation. As the riverbed rises, it would exacerbate upstream flood disasters. Additionally, the discharge of floodwater and sediment downstream would disrupt the existing riverbed structure in the lower reaches of the Great Bend, intensify the rate of riverbed incision in the large bend of the river, and increase the occurrence of landslides and rockslides in the Great Bend (Li Zhiwei et al., 2015). Moreover, the reduction in sediment transported to the Brahmaputra-Ganges Plain is a cause for concern due to its potential negative impacts on the downstream river environment.

- The diversion of water for hydropower generation in the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo River will significantly reduce flow and water levels in the river section from Paizhen in Milin County to Xirang in Motuo County, which forms the large bend of the river. This will have a major impact on the riverbed structure and the ecological environment in this river section. Moreover, it will increase the slope of the rivers along the length of the Palong Tsangpo and Yigong Tsangpo rivers that converge into the Yarlung Tsangpo River at the top of the Great Bend. This increased slope will enhance the river’s erosion capacity and contribute to the geological instability of the Palong Tsangpo and Yigong Tsangpo rivers’ surrounding environment.

The negative impacts on the geological environment mentioned above have been proven in many examples of cascade hydropower development in western Chinese rivers. However, the geological instability and susceptibility to geological disasters in the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend are far greater than in other existing rivers and sections in western China. Therefore, developing hydropower in the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend and constructing mega-engineering projects will incur unprecedented costs and face unprecedented risks.

In terms of Tibet’s own energy needs, there is no requirement for constructing mega-hydropower stations in the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend. Even when considering the possibility of transmitting electricity from Tibet to other regions (such as eastern China), there are significant challenges related to high transmission costs. Given that hydropower stations in Sichuan and Yunnan provinces have to release excess water without generating electricity, there appears to be a lack of demand in the electricity market. In view of the immense negative impact on the ecological and social environments in the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend, and the southeastern Tibetan region, it becomes clear that pursuing hydropower development in this area may not be worth the cost.

However, the allure of increased GDP, investment, and tax revenue generated by mega-hydropower projects can be tempting for governments and vested interest groups. Therefore, the potential environmental and societal risks resulting from flawed decision-making should be a cause for significant concern and scrutiny.

_________________________________

[1] About China’s electricity supply and demand

China’s continuous expansion of installed electricity generation capacity ensures that the growth in electricity supply exceeds the growth in electricity demand and there is no nationwide shortage of electricity. However, there are still periodic shortages during peak electricity demand periods, such as the winter heating season, or in regions which are heavily reliant on sources of power that are variable, such as hydro, wind, and solar power. For example, in regions like Sichuan, where hydroelectric power dominates, shortages may occur during periods of low river flow, requiring stable sources of power from coal or other forms of thermal generation to compensate and regulate the grid, contributing to the sustained growth of coal power in China’s energy mix.

Therefore, considering China’s abundant coal reserves and the stable output of coal-fired power plants, the country continues to rely on coal for electricity generation. Current localized electricity shortages are more related to the variability of energy supply than a lack of overall generation capacity. Even in the case of coal power, China’s dependence on imported coal from Australia, known for its high quality and low-cost thermal coal, contributed to an electricity shortage when diplomatic tensions led to a disruption of Australian coal imports. Once domestic coal production increased and coal imports from Australia resumed, such electricity shortages were alleviated.

Meanwhile, large-scale hydropower development plans in Tibet are primarily driven by the interests of the hydropower industry and the local government’s pursuit of GDP growth and tax revenue. These plans are not needed for more power or to reduce emissions.

[2]While overall electricity demand is expected to grow (unless the economy experiences complete stagnation and negative growth), China’s continuous expansion of installed capacity ensures there is no nationwide shortage of electricity. The relatively high cost of long-distance west-to-east power transmission from hydropower sources is a significant factor restraining demand for hydropower from western regions in China’s eastern provinces.

China exports electricity to other countries, but the proportion of exported power to total electricity generation is small: In Yunnan Province, for example, in 2017, total electricity generation was 273.009 billion kWh and only 2.49 billion kWh of that was exported to Vietnam (1.32 billion kWh), Laos (0.33 billion kWh), and Myanmar (0.84 billion kWh). Though more recent data is not available, I believe that any exports are unlikely to constitute a significant market for Chinese electricity. Yunnan did, however, export 123.17 billion kWh (or 45% of its total electricity generated) to other provinces in eastern China through West-East Power Transmission Grid, to Guangdong Province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in particular. It is interesting to note that 227.763 billion kWh, or 83%, of Yunnan power was hydroelectric power.

Regarding the power transmission grid, China already has a unified ultra-high-voltage grid, but the establishment of a nationwide extra-high-voltage grid has been under discussion. While an extra-high-voltage grid could enhance transmission capacity, the high construction cost, poor economic viability, and significant safety concerns have led many experts to oppose its implementation, making it currently unlikely.

[3]A syntaxis is an abrupt major change in the dominant orientation of the main fold and thrust structures in an orogenic belt.

[4]The Late Cenozoic era, also known as the Neogene and Quaternary periods, is a major division of geological time. It is the most recent era in the Earth’s history, spanning some 23 million years ago to the present day.

[5]“The Catalogue of Chinese Historical Strong Earthquakes from the 23rd Century BC to 1911 AD” was published by the China Seismological Press in 1995; part one of the fourth edition of “The Catalogue of Chinese Earthquakes”. This historical earthquake catalogue covered a time span of more than 4,100 years, from the 23rd Century BC to 1911 AD. It contains 1,034 historical earthquakes with magnitude greater than 4.7. Part two of the fourth edition of “The Catalogue of Chinese earthquakes” — “The Catalogue of Chinese Present Earthquakes” — was published by the China Science and Technology Press in 1999. This catalogue covered the time period 1912-1990, and listed a total of 4,289 earthquakes. See: Methodology to determine the parameters of historical earthquakes in China.

[6]Seismic intensity is a way of measuring or rating the effects of an earthquake at different sites – the degree of damage on the earth’s surface and to man-made structures, such as dams and buildings, for example. Intensity ratings are expressed as Roman numerals between I at the low end and XII at the high end. Signs of building damage for seismic intensity IX: brick (earth and stone) wooden structure houses mostly destroyed and severely damaged; through type timber frame houses a few destroyed, most severely damaged and moderately damaged; fortified brick and concrete structure houses mostly severely damaged and moderately damaged, a few slightly damaged; unfortified brick and concrete structure houses a few destroyed and mostly seriously damaged and moderately damaged; most of the houses with reinforced concrete frame structure are seriously damaged, most of them are moderately damaged and slightly damaged.

[7] A debris flow is a mixture of water and particles driven down a slope by gravity. They typically consist of unsteady, non-uniform surges of mixtures of muddy water and high concentrations of rock fragments of different shapes and sizes. Debris flow differs from landslide in its “flowing” feature. Flow means relative movement in numerous layers of the medium, whereas a slide occurs only along one or several interfaces or beds.

[8] Usually, this dam is referred to as the Motuo Power Station, which is actually a hydroelectric complex, consisting of a high dam upstream for water storage, three massive pipelines for water diversion, and six downstream power stations. According to the data obtained by the author, the total installed capacity of the Motuo Power Station is 43.8 million kilowatts, but there are also articles that mention a total installed capacity of 60 million kilowatts. Both of these figures are unofficial because Chinese authorities have not publicly disclosed relevant data.

[9] Based on the study, “Earthquake Hazards and Large Dams in Western China,” by John Jackson for Probe International, the construction of more than 130 large dams in a region of known high seismicity represents a major experiment for China with potentially disastrous consequences for its economy and citizens. A comparison of more than 130 large dam locations to seismic hazard zones, for dams that are already completed, currently under construction, or proposed in western China, reveals 48.1% of these dams are located in zones of high to very high seismic hazard, the majority (50.5%) are located in zones of moderate seismic hazard, with only 1.4% are located in zones of low seismic hazard. Moreover, the rapid rate of construction and the location of some of these dams around clusters of M>4.9 earthquake epicenters, from events that occurred between 1973 and 2011, is cause for significant concern. The risk of earthquake damage caused by the region’s high natural seismicity is compounded by the risk of Reservoir Induced Seismicity (RIS) which results from the seasonal discharge of water from the region’s reservoirs. The risk of earthquake damage to dams is also compounded by the increased risk of multiple dam failures due to the cascade nature of dam spacing.

_________________________________

References

Liu Yuhai, 1985, A study of the macroseismic damage and intensity characteristics of the Motuo 8.5-magnitude earthquake, Seismological Research, 8(5): 477-483.

You Zeli, Wu Zhixiong, Xie Lejin, 1991, Distribution of intensity of the 8.6-magnitude earthquake in Zayü, Tibet, Northeastern Seismological Research, 7(1): 94-102.

Liu Yan, Wolfgang, Wang Meng, 2006, Research on the internal deformation process of the eastern Himalayan structural knot, Acta Geologica Sinica, 80(9): 1274-1284.

Yuan Guangxiang, Wu Qi, Shang Yanjun, et al., 2010, Regional engineering geology of the northern section of the Yarlung Tsangpo River Great Bend and its influence on the development of geological hazards, Geological Hazards and Environment Preservation, 21(3): 34-41.

Yu Guoan, Wang Zhaoyin, Liu Le, et al., 2012, Development of the Yarlung Tsangpo River system and characteristics of river morphology under the influence of new tectonic movement, Advances in Water Science, 23(2): 163-169.

Wang Zhaoyin, Yu Guoan, Wang Xuzhao, et al., 2014, Influence of the uplift of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau on sediment transport and geomorphic evolution of the Yarlung Tsangpo River, Sediment Research, (2): 1-7.

Li Zhiwei, Wang Zhaoyin, Yu Guoan, et al., 2015, Influence of Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend hydropower development on slope stability, Journal of Mountain Science, 33(3): 331-338.

Xie Chao, Zhou Bengang, Li Zhengfang, 2017, Morphological characteristics of the East Himalayan structural knot and their tectonic significance, Journal of Seismological Research, 39(2): 276-286.

Zou Zinan, Wang Yunsheng, Xin Congcong, et al., 2019, Analysis of influencing factors of high-altitude rockslide in the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend, Journal of Geological Hazards and Environment Preservation, 30(1): 20-29.

Li Xiang, 2019, Development of large-scale landslides and new tectonic landforms in the Yarlung Tsangpo River section of Motuo, Master’s thesis, Chengdu University of Science and Technology.

Li Bin, Gao Yang, Wan Jiawei, et al., 2020, Current status and countermeasures of the development of special geological hazard chains in the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend area, Hydropower and Pumped Storage Energy, 6(2): 11-14.

Fan Xiao, a Chinese geologist and environmentalist, is the retired Chief Engineer of the Regional Geological Survey Team of the Sichuan Geology and Mineral Bureau and a member of the Sichuan Seismological Society.

The original Chinese version of this report is available here: 范晓︱从地质风险的角度谈雅鲁藏布大峡谷水电开发不可行

11 replies »