Despite the success of Beijing’s “blue sky” energy policy, the forced coal-to-gas/electric program has created a significant humanitarian and economic crisis in the rural areas surrounding the capital.

First published on January 12, 2026, by China Digital Times

The original Chinese-language version of this essay has been translated by Probe International with notes added for clarity.

Introduction by Probe International: The rollout of Beijing’s state-led “blue sky” energy policy—part of the national Three-Year Action Plan for Winning the Blue Sky War—has sparked significant criticism for its perceived hard-hearted and unjust allocation of greater subsidies to the wealthy, urban elite, while neglecting the needs of poor and rural populations. This approach exemplifies a longstanding pattern of discrimination against disadvantaged groups in China. Resource subsidies, especially in the energy sector, are fundamentally flawed as they distort decision-making regarding resource use. A more effective strategy would be to provide direct cash subsidies to low-income households, allowing them the autonomy to manage their increased heating costs as they see fit. Meanwhile, the promotion of heat pumps—essentially reverse refrigerators that operate on electricity—raises further concerns. With approximately 60% of China’s electricity generated from coal, these heat pumps are indirectly powered by coal, undermining the intended environmental benefits. Additionally, the high costs associated with purchasing and operating heat pumps make them less accessible for rural communities, who would be better off using coal directly for heating. However, the political implications of air pollution in major cities like Beijing have led the Chinese Communist Party to prioritize urban political stability over the energy security of residents in Hebei.

The Bluer the Sky, the Colder the Homes; The More Presentable Beijing Becomes, the More Icy Hebei Feels (China Digital Times)

The issue of “excessively high rural heating costs in Hebei” triggered the widespread attention of netizens. Images circulated showing elderly villagers in Hebei Province—where Beijing is essentially an enclave—sitting in homes, bundled in thick cotton coats, huddled on heated brick beds, choosing to endure the cold rather than turn on the heating. Such scenes are heartbreaking, yet their cause is both simple and harsh: as government gas subsidies have been scaled back and residential gas prices have risen, many households can no longer afford heating and are forced to endure winter conditions without it.

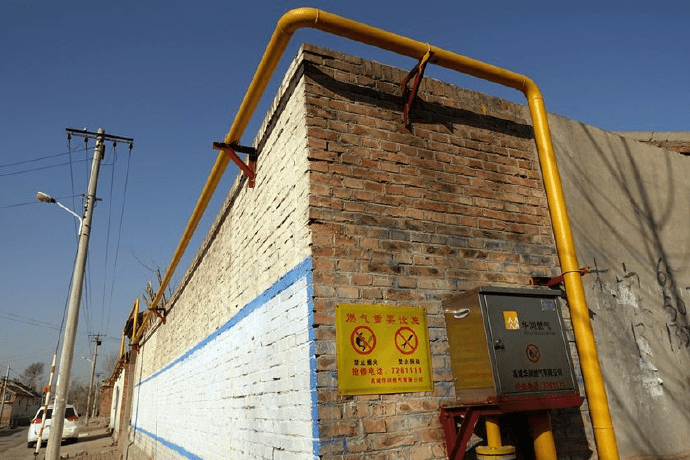

As early as 2013, China began its “coal-to-gas” transition to mitigate the prolonged and severe winter smog in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. Before winter, many households traditionally stockpiled coal for heating, and the burning of loose coal generated high levels of air pollution (“loose coal” or raw coal, sometimes sold as briquettes or “honeycomb coal,” was used for direct combustion in residential homes and small boilers for heating and cooking). In 2017, environmental authorities launched the “Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Air Pollution,” mandating that many areas of Hebei rapidly complete coal-to-gas and coal-to-electricity conversions. This politically charged campaign-style governance led to the dismantling of individual household boilers before replacement heating was available.

Media reports at the time noted that governments at various levels issued substantial clean-heating subsidies, encouraging rural households to cooperate with hardware retrofits.

However, beginning six or seven years ago, rising natural gas costs combined with shrinking local fiscal revenues led to a

gradual rollback of subsidies across many parts of Hebei, driving up the cost of gas for every household. Some governments allowed companies to cut or limit heating supply, resulting in so-called “economic supply suspensions.” At the same time, more and more rural families in Hebei found themselves weighing cold temperatures against household budgets, wavering between not turning on heating at all or using it sparingly. One local people’s congress representative calculated that subsidies in many areas fell from around 1 yuan per cubic meter to 0.8 or even 0.2 RMB (Chinese Yuan). For a typical 100-square-meter rural home in Hebei, maintaining an indoor temperature of 18°C requires 20–30 cubic meters of gas per day, pushing heating-season costs to 7,560–11,340 yuan—equivalent to nearly an entire year’s per capita disposable income for rural residents. Faced with such costs, many elderly villagers simply cannot bear to turn on the heat.

Some households have resorted to secretly burning loose coal, as it remains far cheaper than natural gas. But “defending the capital’s blue skies” has always been a core driver of Hebei’s coal-to-gas policy. Authorities have enforced strict controls, including shutting down coal depots, setting up inspection checkpoints, implementing grid-based monitoring, offering rewards for tip-offs, and deploying drones for surveillance, pushing residents into a dilemma of being unable to afford gas, yet afraid to burn coal. Online users discovered that inspection drones in Hebei are equipped with thermal imaging and spectral analysis technology, capable of round-the-clock detection of “illegal heating.” Many remarked bitterly: there is money to buy drones to monitor people burning coal, but none to provide subsidies. On January 5, Farmers’ Daily published a commentary on Hebei’s rural heating crisis, stating that “we cannot allow the elderly to freeze; people must always come first,” and that “subsidies must provide a basic safety net—villagers should not be pressured to convert only to see subsidies cut afterward.” The article was later removed.

Adding to the irony, some bloggers posted videos noting that in parts of Beijing, electricity and gas costs are actually lower than in Hebei due to vastly different subsidy standards—and that even within Beijing, urban and rural areas operate under separate pricing systems. For years, Hebei has effectively served as a sacrificial buffer for the capital. In May 2019, the provincial party secretary stated that Hebei would “rather sacrifice GDP than ensure Beijing’s blue skies.” [Editor’s Note: Here, Wang Dongfeng, Party Secretary of Hebei Province and Chairman of the Standing Committee of the Hebei Provincial People’s Congress, at a State Council Information Office press conference on May 28, 2019, said that the industrial and energy infrastructure in his province is excessive and not economic, and though it may inflate GDP, he would rather “cut it back, proactively adjust, and accelerate transformation” and “sacrifice GDP to ensure blue skies and white clouds over Beijing.”]

In August 2023, while floodwaters in North China had yet to recede, Hebei’s leadership emphasized the need to “serve as Beijing’s protective moat during flood control.” More than a year ago, netizens exposed the existence of physical barriers between Beijing and Hebei, with the boundary resembling that between two countries. Though framed within a shared regional narrative, Hebei and Beijing are subject to starkly different priority hierarchies: Hebei is expected to submit to the greater good, yet its hardships go unanswered. The bluer the sky, the colder the homes; the more presentable Beijing becomes, the more frozen Hebei feels.

Some argue that Hebei’s coal-to-electricity transition, branded as “clean heating to protect blue skies,” is really about safeguarding Beijing’s air quality and national image—“the cleaner Beijing gets, the harder the surrounding regions must push.” Authorities have imposed blunt, one-size-fits-all measures, disregarding infrastructure realities and residents’ economic capacity, enforcing policies through coercive means that leave many freezing through the winter. This is the reality encapsulated by a popular phrase from 2015—“fascist blue”—a sarcastic reference to skies achieved through administrative force for specific goals or events. Is this not a form of humanitarian disaster? Even if clean-heating reform has its rationale, why must the environmental costs be borne primarily by Hebei’s population?

A public policy aimed at improving regional air quality has had a devastating effect on household energy bills, revealing not merely an energy crisis but a crisis of accountability: those who pay do not benefit, those who benefit do not pay. On social media, users expressed this resentment in blunt remarks that point to a deeper systemic ailment: why must I—or we—be the ones sacrificed? — “So close, yet so beautiful—middle-aged and elderly freezing to death in Hebei.” “After the Three Gorges Dam was built, electricity cost eight cents per kilowatt-hour.” “When it’s time for the government to feast, I’m excluded; when there’s pollution, it’s all on me.” “Too far from heaven, too close to Beijing.”

Go to the publisher’s website here for the original version of this essay.

Categories: China Energy Industry, China Pollution