China’s acclaimed master of independent cinema risks punishment to screen his latest release at Germany’s Berlinale without approval from Chinese authorities.

By Probe International

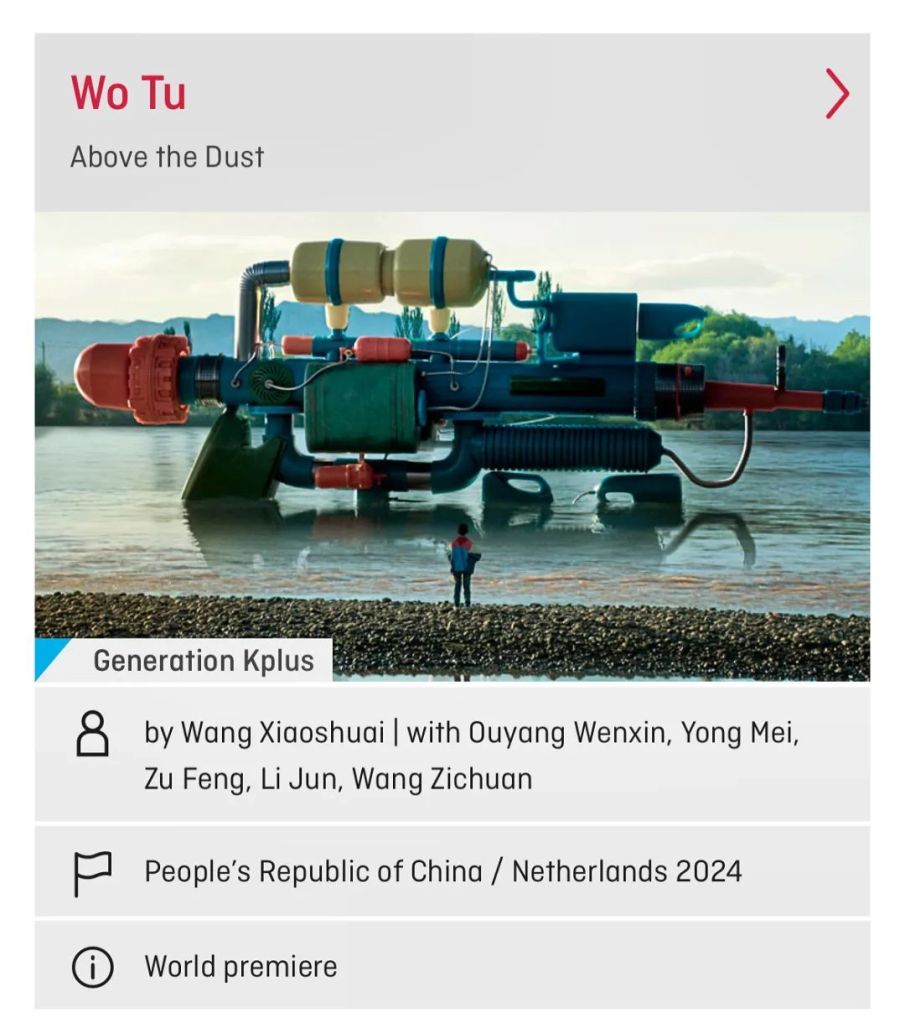

On the eve of the world premiere of acclaimed Chinese film-maker Wang Xiaoshuai’s “Above the Dust” at the Berlin International Film Festival, the US entertainment magazine Variety published two articles in a row highlighting the risk Wang faced if he defied “China’s censorship system with a drama about historical land reform and its deadly consequences.”

The screening of Wang’s first release since his 2019 Berlinale entry, “So Long, My Son,” organizers deliberately downplayed the inclusion of “Above the Dust” to avoid attention. Confirming the film had not secured government approval (via China’s National Film Bureau), organizers told Variety they were willing to proceed if the director wanted to. Without the “Dragon Seal” of approval from China’s film bureau, no release is sanctioned to legally play in Chinese theatres or at overseas festivals.

According to Variety, “Above the Dust” was submitted for Chinese censorship approval in October 2022. Wang attempted to comply with the more than 50 edits and deletions censors required, but after 15 months of negotiations the approval process stalled. Variety notes that “in other instances where Chinese titles without the right permits were selected for major festivals, the films were typically withdrawn by the filmmakers before a public screening went ahead. In 2019, Berlin saw Zhang Yimou’s ‘One Second,’ about the Cultural Revolution, and Derek Kwok’s ‘Better Days,’ about disaffected urban youth, both pulled at the last moment.”

A three-time winner of the Berlinale’s prestigious Golden Bear award [pictured], Wang’s 2019 showing at the festival saw that entry’s lead actors, Yong Mei and Wang Jingchun, take home top honours for their performances. This would rank as the last highlight on the international film stage for China before the outbreak of the pandemic.

“Above the Dust” is the second installment of what Wang refers to as his ‘Homeland Trilogy’ examining China’s changing times and families for the past 40 years. The first, “So Long, My Son,” explored the personal and social effects of China’s one-child policy introduced by the government in 1979, and reversed in 2015 after it became apparent the policy might have succeeded too well.

Based on a short story by Li Shijiang, “Above the Dust” tells the tale of what China has lost in its drive for modernisation. Set in 2009 in an impoverished village in the country’s northwest, the story centers on 10-year-old Wo Tu as his family comes to grips with rapid urbanization and rural displacement. As neighbours slowly migrate to the city, the boy’s parents search for family heirlooms buried in the surrounding land. Through magic realism, Wo Tu is able to communicate with the ghost of his grandfather and learn about reforms that forced peasant-owned land transfer to the government as part of the Great Leap Forward, the disastrous political-economic plan implemented by Mao Zedong from 1958 to 1961, and the cause of tens of millions of deaths from famine and disease.

Speaking to Variety, Wang (considered the father of China’s modern independent cinema) said he saw his work as a way to advocate for freedom of expression.

“Since we make films for audiences, first of all for Chinese audiences, I really hope that my film can be seen by Chinese audiences, legally and publicly.”

Wang added that official censorship breeds self-censorship.

“[But] with the long-time suppression that comes from censorship, it is quite difficult to open your mind to create freely. When I have a story to tell, I have to think about censorship first, which kills my own creativity and ability to express things,” he said.

Incongruously, Germany’s Berlinale selected to play “Above the Dust” in its Generation Kplus section, which screens films for or about children. In his conversation with Variety, Wang notes:

“Firstly, I don’t think it’s really about children. I think [land reform] is a large subject, and difficult to explain. After ‘So Long My Son,’ this is about workers and peasants in China. And what has happened to them. China has had such rapid urbanization, and so I wanted to tell about what happened in the countryside.

For a long time I knew that I wanted to do this. But I could not find the right story for it. I read a lot about it. Learned how nobody was looking after the land. It seems that one reason was that the peasants didn’t have their own land. They could not make a living just waiting for the harvest and had to go into the cities for work.”

Referring to the film showing without approval, Wang told Variety:

“There’s pressure on the production company and myself. A lot of pressure. It is forbidden to show the film without a Dragon Seal in Berlin. But Berlin selected it. I’m happy about that. This is the film that I wanted to make. About China, about our lives. About Chinese history and reality.

I should be happy that the film can make its world premiere somewhere like in Berlin. But I have to face pressure first, not knowing exactly what will happen later. According to Chinese regulations, if my film goes to a festival like this without the Dragon Seal, I’ll be punished.”

Despite the risk, the Berlinale’s showing of “Above the Dust” went ahead for the length of its run from February 17 to February 20. Among the reviews published following its debut, Beijing’s state mouthpiece South China Morning Post ran one of its own, describing the outing as “Christopher Nolan-like” for its dramatic visual design. The Post, however, found Wang’s “tried-and-tested brand of social realism” a “mundane” drag on an effort otherwise deserving of “some praise”.

The censorship struggles that plague China’s creative community are nothing new. In 2009 — the same year as Wang’s timeline for “Above the Dust” — the Chinese guests of honour scheduled to attend a symposium hosted by the Frankfurt Book Fair, found themselves in the middle of a firestorm when the Chinese government threated to boycott the event if the headliners were allowed to participate.

Legendary investigative journalist, Dai Qing, and Bei Ling, a renowned poet, essayist and founder of the Independent Chinese PEN Center, were even disinvited after the government’s response triggered an internal debate among the fair’s organizers. The German side withdrew their invitations to Dai and Bei but their actions were seen as “bowing to bullying” and provoked a public outcry.

In the end, Dai and Bei went ahead with their scheduled appearance at the symposium, somewhat ironically focused on creating dialogue about domestic and international perceptions of China in the 21st century. Predictably, the bulk of the Chinese government delegation in attendance walked out, agreeing to return only after Dai and Bei left the conference venue.